By Toyin Falola

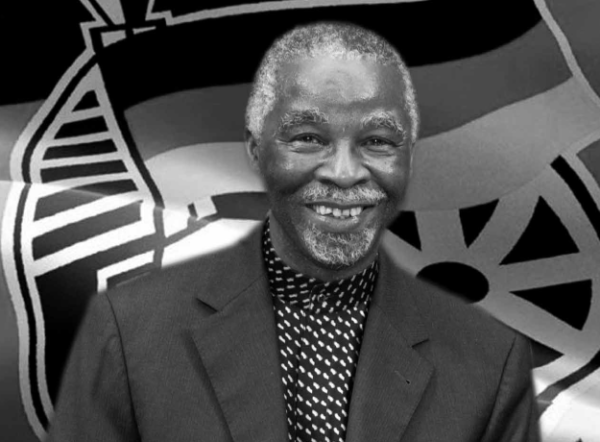

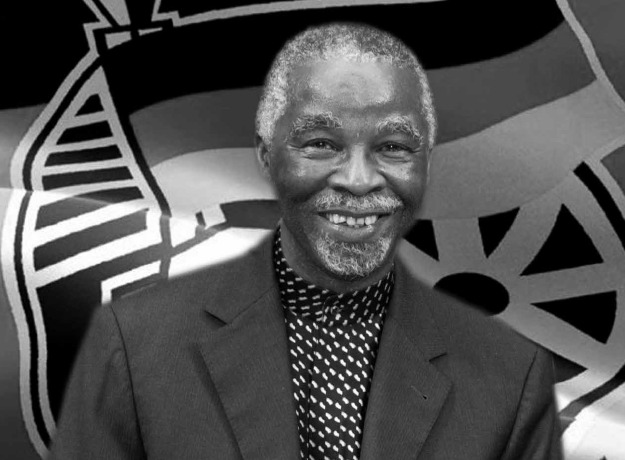

Global politics today is a representation of what happens in the core jungle where the powerful eats the powerless. Since the authority and hegemony to eat or be eaten has been carefully configurated into a hierarchy evinced in political systems, we often downplay how wild and sometimes horrific geopolitical behavior has become. I think the two institutions named after Thabo Mbeki at UNISA clearly understood it. The original TMALI clearly understood how African thought systems can be weaponized to fight oppression, injustice, and domination and how the Thabo Mbeki School is to escalate the power of the African agency. It has been a rare privilege for me to have been associated with both institutions and be part of the initial planning of the Thabo Mbeki Museum. In the planning sessions of the Mbeki one, I argued that it should not replicate that of the President Olusegun Obasanjo library for reasons that space does not allow me to state here.

No better way can the hegemonic attitude of global geopolitics can be described than the symbolic reference that George Orwell makes in his avant-garde literary production, Animal Farm, when exposing the double standard of the pigs who, after wrestling power from the anarchist humans, who, according to them, became an impediment to their blossom. The pigs became overly sensitive and dictatorial, forgetting, for example, that the foundation of their ascendancy is built not on their imagined strength but on the goodwill of different individuals who recognized the need for radical changes and were determined to play their part. Meanwhile, after they assume power, the assemblage of their administrative team oozes segregation and apartheid, so much so that the members who took an active part in the rising of their group became apprehensive, and that was justifiably so. What other evidence do they need to conclude that their leaders (the pigs) were becoming utterly intolerant and excessively power-drunk other than the constitution of administrative members and the exclusion of vital members of the animal family? The book Animal Farm is an allegory of capitalism’s desire to destroy socialism. Africa has yet to construct its allegories to destroy the powers that destroyed them. What you find in Mbeki’s letters are ideas for embarking on rescue operations.

Interestingly, the pigs have not forgotten that the epochal events that led to the ousting of humans from the power bloc are potentially going to raise their ugly heads at any point in time, but their intelligent memory does not prevent them from being self-centered, self-serving and totalitarian. The Yorùbá forebears are clairvoyant in that they already foresaw the possibility of such very antisocial behaviors that they coined a saying that “a be’ni lori, kii fe ki ida gba ori oun koja” (“A hangman abhors people swinging swords over his head”). Yorùbá elders are wise because they know that, like the proverbial hangman, the pigs would not want any act of insurrection, for they would immediately see that as an attempt to dislocate them from the most revered seats of power where they enjoy almost everything that they desire.

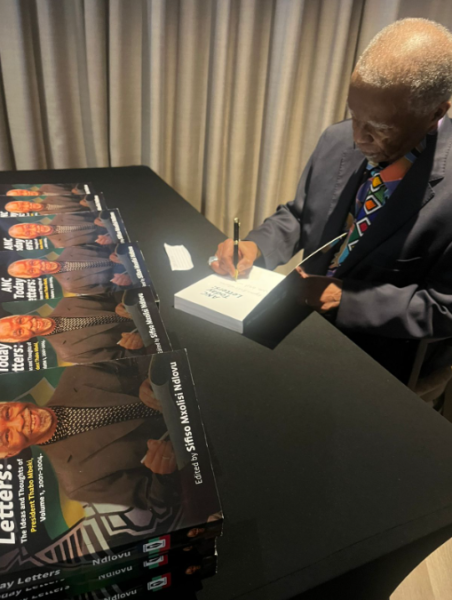

The above aptly captures what Thabo Mbeki describes in his series of letters, documented in this context under the published work edited by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu. The white minority is perpetually overcome by fear and trepidations because they have seen the rays of conservative attitude and its implications to foreigners in Zimbabwe, and they are jittery as they do not want that replicated in what they now call their “home.” Anyone familiar with the ongoing jittery of this minority may not understand the context of their fear, even though the preliminary introduction above should have given some signals. Let us travel down the history lane.

The ascendancy of the West to the forefront of global relevance politically, economically, and even ideologically comes from their steady despoliation of many other civilizations through forceful conquests where necessary, and subtle takeovers where diplomacy worked. Of course, the Greeks and the Romans, Africans, and the Arabs all have recorded measurable progress and dominated global politics through the various activities associated with them, such as the spread of knowledge, the possession of strong armies, and the making of bold steps to improve themselves. However, Europeans desired such development, as every animal does in the jungle, but it did not seem that they would attain their objectives with the present configuration of things.

Voila! They made inroads in technology, and that became the very foundation of their emergence. Whereas Africans were consolidating their knowledge on communities and positive living (a point I repeatedly emphasize in my annual lecture at the University of Pretoria as part of the well-articulated lectures organized by the super talented Professor Chris Isike), Europeans were developing ideologies and technology of conquest and control. This technology specifically brought them superior power as they invented guns that would be valuable in silencing dissents and objects such as trains, ships, and vehicles that would convey them to a very distant geography in which they spread their influence and expansionist gospel. Millions of people died, civilizations crumbled, and generational accomplishments were shattered at the sight of the ambitious Europeans. In Africa, that colonial dream manifested in the whites settling in some areas of the continent, two examples of which are South Africa and Zimbabwe. Institutionally, they imposed themselves and made frantic efforts to dispossess people of their ancestral heritage: land, homes, culture, and values.

With independence, however, which came very late in the two countries cited above, the black population was gradually getting its feet back, but they both have different ways of handling their historical experience in the current time. Mention should be made of how the white minority had appropriated to themselves the larger portion of land in a proportion that cannot but rupture peaceful minds. A population that was lacking in numerical strength has allocated to itself so much that the population is the larger and natural occupant of the geography. If it was inevitable that the condition of colonialism and apartheid necessitated that Zimbabweans and South Africans would have to live in peace with their white oppressors, it was, however, avoidable to do that in terms of the now-supplanted minority. That perhaps was what motivated the erstwhile Zimbabwean President, Robert Mugabe, who radically pursued the ambition to have their land retrieved and redistributed back to the rightful owners. Of course, he did not impose a policy to evacuate the white minority. Still, he could not stand the prospect of seeing them having access to larger assets after years of oppression, their blatant epistemicide, and the detention of freedom fighters, among others. Still, Mugabe was indeed not going to allow the West to dictate the tenor of his government, especially how it concerned sharing their ancestral legacy because not only is that act inherently brutal, but they also have now seen the light of freedom after centuries-long maltreatment from the white minority. No wonder Zimbabwe under Mugabe experienced sanctions upon sanctions by the West, who felt he had become uncontrollable and dangerous to the colonial project of the European expansionists.

Meanwhile, the same Yorùbá people have etched another important lesson in their saying that “iku to npa jugba eni, owe loan pa fun ni” (“the death that takes the life of one’s kindred is sending a signal to one”). The white minority in South Africa is perpetually fearful and apprehensive about the development in Zimbabwe, and to alleviate their fears, they have often made alarming propositions that the government of South Africa under Thabo Mbeki should denounce Zimbabwe. They calculated very well that unless such effort was made at the political level, they could not be certain of what was to come to them, especially if South Africa produced a leader such as Robert Mugabe. In denouncing Zimbabwe, they are not particularly interested in the repudiation of the country per se; they are only concerned about the optics it would bring to the political atmosphere, which, at the zenith, would indicate that the black leadership in the country would nurse no interest of dispossessing them of their land and their “hard-fought”economic resources and that they would remain secure in any case of emergency. Of course, the paradox of that cannot elude anyone familiar with the history of apartheid in South Africa, but more than that, it would be a seismic irony that the population of a people who threw morals and empathy through the window when forcefully dispossessing Africans of their ancestral legacy, is now projecting the need for tolerance, integration, and inclusiveness. What a time to be alive!

Athol Fugard will be marveled that the same South Africa where blacks were generally disempowered from having access to decent job opportunities, a fate imposed by the white minority during the apartheid regime, is the place where black African leaders are now gaslit to embrace liberal values in order to accommodate disparate voices and give room for multicultural identity so that the majority would not threaten the interest of the minority. Meanwhile, Thabo Mbeki is direct when he argues that the foundation of tolerance and inclusiveness, which is observable in the South African politics of today, is a brainchild of the efforts made by seasoned black South Africans who gave up their freedom for the emancipation of all. These individuals were subjected to inhuman torture, contempt, and cringing racial discrimination that took away their integrity, but they gave all in the expectation that such sacrifices were necessary if they would see to the rise of their generations to come where decisions are made. Terrible as it appears, the conduct of Robert Mugabe and his very controversial stance towards the white minority reminds everyone of the outrageous processes of dispossession that Africans were forced to go through in their recent history. The proverbial hangman of the white minority abhors people swinging swords over their heads, after all. To unpack my statements, you must read Ndlovu’s book and the Mbeki letters and writings curated in the museum created in his honor.

PS: This is a 12-part series based on the collections edited by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, titled ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004, supplemented by materials in the Thabo Mbeki Museum, UNISA, Pretoria. The series is composed over five weeks in three different countries. The museum’s resources, digitized under 27 categories, can generate over 200 books.

The South African case is very distinct from how former Rhodesias were built. Semblance of Favela existed in South Africa where the Rhodesias seem to be a case of Lagos type of experience of very distant EUROPEAN settlement and African rural settlement. Like, be where you are when we need you we negotiate on how your physical strength could be employed and you come and go.