By Toyin Falola

As the 20th century announced its permanent departure, African leaders became apprehensive and positively so. The continent had experienced destabilizing economic tides, largely due to the not-so-palatable input of the Western global capitalism who plunged and extracted Africa’s resources to the brink of collapse. However, the new dawn following the dark era of colonialism and its aftermath presented new opportunities. African leaders were now expected to make realistic plans to safeguard their people from potential economic disasters that might persist into the next decades.

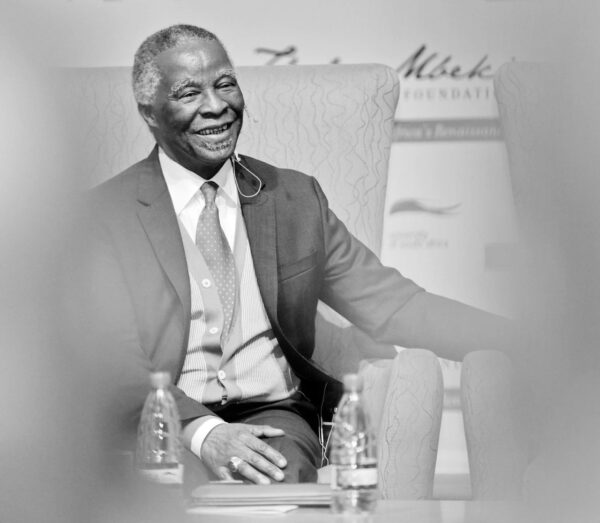

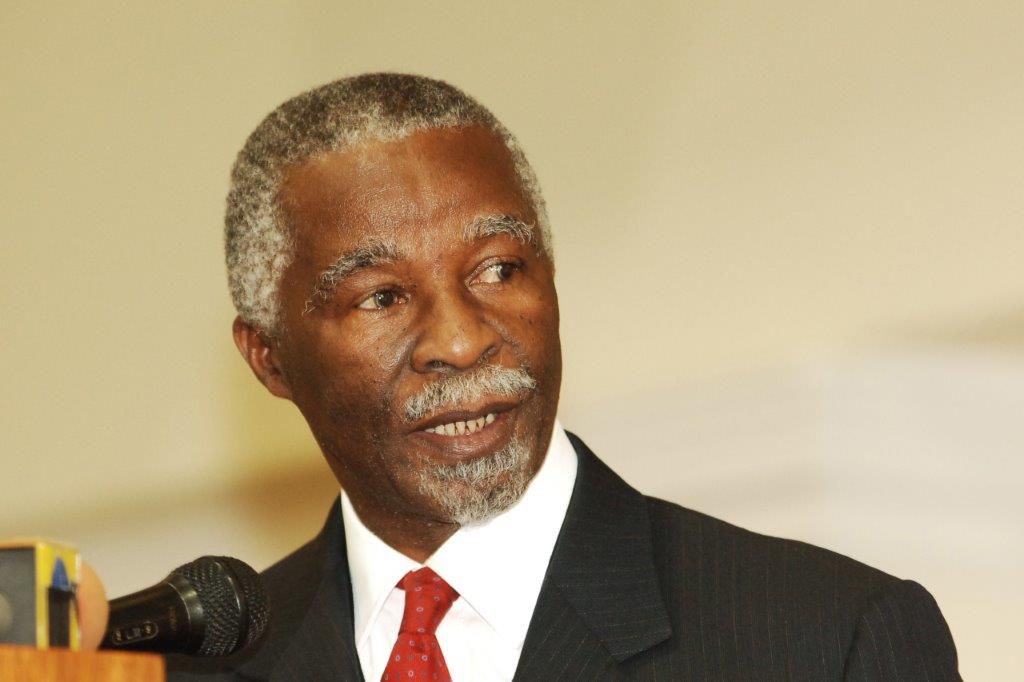

Thabo Mbeki highlights the proactive role of African leaders in seeking domestic and international support for the revival and rejuvenation of the African economy. The leaders spoke about leveraging their positions to galvanize necessary support from international institutions, demonstrating their unwavering commitment and discipline. The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was deployed as the agency through which they could initiate recovery plans. Bold policies were implemented to attract the private sector to play crucial roles in their economic retrieval plans. This proactive approach saw the persistent projection of African core economic and financial crises where necessary, with a view to encouraging resourceful ideas from allies who could help address their existential problems.

Mbeki intones that the first critical point of agreement among the leaders was the need to ensure peace across every part of the continent. This was premised on the conviction that economic recovery holds greater potential only in a peaceful environment. In essence, conflict, strife, controversy, and crime are naturally repellent to progress. Therefore, for Africa to secure a place on the global stage, where economic power and growth are cardinal, it needed to avoid the disruptions and setbacks caused by various altercations. The efforts demonstrated by African leaders immediately following the 20th century clearly indicated that they belonged to the same school of philosophical thought. This was underpinned by their common desire to rid the continent of poverty and introduce great ideas that would restore economic justice to people who had previously faced significant challenges. These leaders understood that peace is essential for the possibility of attaining unfettered democracy, as it creates an atmosphere for the exchange of ideas and values to the extent that they would add impact to people and their undertakings. Mbeki is very committed to such an engagement, driven by the belief that South Africans deserved the quality of life that had been earlier denied to them because of apartheid.

In their sagacity, African leaders concluded that the best way to improve the conditions of the continent was by enhancing the quality of life. They recognized that one of the most effective ways to actualize economic justice was to ensure that individuals were equipped with the mental resources needed to thrive and become more influential wherever they found themselves. The assemblage of these leaders led to the implementation of the right ideas and policies aimed at the reorientation of Africans about themselves, their continent, and how they interact with others. However, this would remain elusive if they did not harness their internal potential to their advantage. The leaders understood that African values needed to be strengthened to prepare the people for the world’s challenges and issues. Consequently, they promoted an attitude that could positively and productively transform lives. Before realizing such lofty ambitions, the leaders also understood the importance of prioritizing their people by ensuring access to a quality life, improved standards of living, and institutional benefits.

While it is the citizens’ responsibility to make themselves valuable, the government’s role is to provide the institutional benefits necessary to help them become responsible individuals. Interestingly, the African leaders were ready to do even more. Mbeki understands that while a larger percentage of Africa was subjected to colonial destruction, different colonies nursed variegated pains. In the case of South Africa, for example, it is common knowledge that the dispossession of their lands and immobile resources led to a significant reduction in the quality of life for the South African people. The forced takeover of their land and the implementation of hostile and horrific policies changed the course of all Black South African people. To change that fate, it was imperative that they urgently find ways to reclaim their land on a large scale, and their resources must also be kept in their hands for good. This would create an environment for the rejuvenation of their economic power and, by extension, restore their lost glory.

Although Mbeki’s focus is primarily on the South African people, he also envisions similar things to be replicated across different African countries, believing that such measures would bring about economic emancipation and make the people relevant in the scheme of things. In ways that no one would have imagined, African leaders began their efforts earnestly, bringing renewed hope to Africa by repudiating the hegemonic economic policies that had previously stifled their progress. With access to land and basic amenities, the people embarked on a journey toward quality existence, supported by helpful leaders committed to accompanying them on that journey.

Mbeki reveals that while the above plans hold great promise for African emancipation and liberation, they can be complemented by a more important strategy that would accelerate their rise to prominence. Immediately after the world entered the 21st century, the culture of globalization became pronounced, driven by the emergence of technologies that collapsed physical boundaries and created boundless virtual geography. It was like an epiphany for Africans, as they were not only experiencing the independence of their countries from the imperial Europeans but also being ushered into a new world of technology where connectivity and interactions are possible and unrestrained.

Regrettably, Africans were not actively involved in this technological transformation because they were not particularly instrumental in the development of technologies that necessitated it. Nevertheless, they had to prepare for life in a digital world. Pre-empting this possibility was what informed the African leaders of the time to incorporate digital programs into their activities, ensuring that Africans could navigate their existence in the digital realm just like their counterparts. This was underscored by the awareness that in a digital society, people could engage in economic activities and earn from it, strengthen their social interactions to create lasting networks, and pursue their ambition more effectively, which laid the foundation for their organizational behavior.

For Mbeki, one of the most critical steps the government needed to take was implementing policies aimed at the eradication of poverty in the country. He believes that unless poverty is reduced to the barest minimum, racism and discrimination will continue unabated in the country. To confront the problems that could arise from economic disparity, it was essential to integrate South Africans into the economic structures of society so that they could access the necessary resources to lift themselves out of poverty. With this, it was non-negotiable that Black South Africans be brought back to the table to bridge the gap created by the apartheid regime.

Previously, developmental opportunities were distributed without fairness, and the deliberate disarticulation of African woes and the relegation of their concerns to the background severely affected economic justice in the land. Black South Africans were relegated to a helpless category, where millions did not have access to wealth and resources and were deprived of leadership empathy that could have alleviated their plight. During Mbeki’s rule, he spoke to the ideas of ensuring that such inequity disappeared flagrantly, gradually but consistently.

PS: This is a 12-part series based on the collections edited by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, titled ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004, supplemented by materials in the Thabo Mbeki Museum, UNISA, Pretoria. The series is composed over five weeks in three different countries. The museum’s resources, digitized under 27 categories, can generate over 200 books.

This is no doubt another brand of Falola-esque ambitious historical, political and economic surveyor of Africa’s experience in its march through the 20th century crises in search for development. It is worth reading the different interpretations of the variated junctions of African leaders’ sterile seeds on the fertile soil of Africa’s natural assets of wealth – climate, land, water, flora, fauna and free airspace. Quite rightly, Professor Emeritus Toyin Falola is a scientific historian whose objective critical lens is never emotionally inclined as a lethal cudgel against leadership aberrations, even though he does not privilege them. He engages a seeming intellectualization of historical justice and knowledge in attempt to assign privileges in otherwise unprivileged accounts of journalistic social scientists.