Toyin Falola

This piece is to celebrate the teaching award to be conferred by the University of Texas at Austin on Professor Niyi Afolabi, my colleague, on April 23, 2025. I wish I were to distill my skills as a biographer and start this narration at Ile-Ife, Nigeria. No, this won’t work well. Let me start at the current moment.

The fatalities of Eric Garner and Michael Brown became major turning points for global African and African American concerns. The “Black Lives Matter” campaign gained global recognition in 2014, especially after George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody. The movement challenges discriminatory actions against African and African American people, and the #Black Lives Matter campaign has prompted recent protests against racial injustice and police brutality, as well as Black community marginalization. Afolabi’s scholarship, drawing massive data from Brazil, is based on racial, national, and communal marginalization

Marginalization has always been a common social problem for a long period in Africa and its diaspora. Apart from the general marginalization resulting from slavery and colonialism, many African nations are products of ethnic diversity, therefore enabling internal marginalization. Nevertheless, marginalization is a broad concept encompassing ethnicity, socioeconomic level, gender, and, sometimes, race. For example, women are stereotypically seen in many parts of Africa as second-class citizens, judged unworthy of quality education and economic opportunities. Conversely, poverty and economic inequality result in conflict in a society. Like ethnic and social marginalization, racial marginalization is also common in many African countries, particularly among people once under slavery and colonialism. Am I talking about Afolabi? Yes, as these are some of the tropes that influence his thinking processes, well articulated in three books on Brazil.

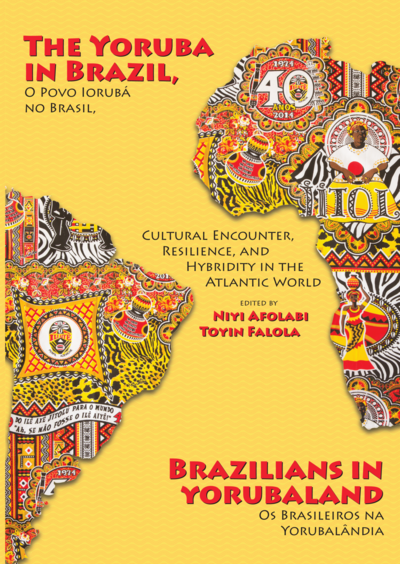

There is no doubt that many African scholars have tremendously contributed to the emancipation of the continent from colonial dictatorship and mentality. Professor Afolabi has established himself as one of the academics who duly follow this path by positioning himself as a catalyst for social and global change. His book, The Yoruba in Brazil, Brazilians on Yorubaland: Cultural Encounter, Resilience, and Hybridity in the Atlantic World,” examines the cultural dynamics and resilience of the Yoruba people in Nigeria and Brazil. Afolabi’s concerns as a Nigerian of African descent are especially articulated in the book’s depiction of the Afro-Brazilian Yoruba experiences of discrimination and prejudice.

The marginalization of the Yoruba community in Brazil due to the hostility from Pentecostal Christians undermines the belief that Brazil is a secular state. Not only this, but he also elucidates the power tussle and sheer arrogance that exist between the Yoruba in Nigeria and their counterparts in Brazil. This is from the perspective that Brazillian returnees are influenced by Western culture, hence undermining the originality and authenticity of our norms in Africa. This position has caused the Yoruba community in Brazil to experience a sense of identity loss, leaving them uncertain about where they truly belong. Omowale, a nickname I am deploying for Afolabi, relocated from Ile-Ife to Ile-Aiye in Bahia. The choir boy is now carrying akaraje to the Irunmole!

But how long have the African cultural practices persisted in the context of current globalization? This poses a question of resilience regarding the survival of African culture in the face of slavery and colonialism. It is quite understandable that we inhabit a society where the Western culture is ridiculously dominant, and how the Afro-Brazilian culture has managed to thrive remains mysterious. This mystery is what Professor Afolabi has dedicated his time and efforts to unravel and demystify through his scholarly lens. He thereafter posits that the answer lies in the complexities and intricacies of racial and cultural identity and perhaps the power dynamics in the West. I will offer a critique of his powerful postulations at another time.

Although Brazil claims to be a racially democratic country, the unfortunate reality is that white supremacy is a prevailing ideology in the society. This helps to make clearer the factors contributing to Afro-Brazilian marginalization and exclusion. Even though there were power relations already in place in Brazil, Afolabi powerfully analyzes a clash between racial equality and the dominance of the white people, hence condemning racial discrimination within the nation on the grounds that it stifles the development of individual culture instead of promoting syncretism.

An African proverb states that a river does not forget its source. This may explain why Afolabi dwells on the significance of African practices, such as rituals, ceremonies, and other spiritual practices, which cannot be underestimated in the lives of Afro-Brazilians. These practices remain a vital point of Afro-Brazilian cultural identity and a sense of connection to their African roots.

There is no gainsaying that Afolabi is one of Nigeria’s finest scholars in the same league as those in the front rank who have contributed to the growth and development of literary appreciation. Starting his academic journey from Ile-Ife, where he studied Foreign Languages (French and Portuguese), he became familiar with different foreign cultures before pursuing a career in Luso-Brazilian Studies, where he had the opportunity to explore the nexus between the cultural practices in Portugal and Brazil. This field has also afforded him the opportunity to emerge as a prominent voice in Afro-Brazilian relations. As a hyperpolyglot, he is fluent in Yoruba, his native language of southwestern Nigeria; English, the official language of Nigeria; French and Portuguese, which his academic journey began at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

To attest to his leadership qualities and experience, Professor Afolabi has held numerous positions and served in different capacities. He is currently a professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is leaving his footprints on the sands of time. Moreover, Professor Afolabi has won several research grants and awards. Furthermore, as evidence of his significant contributions to African and African Diaspora studies, he has been honored with the award for John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies Research Award at the University of Texas at Austin.

The nomination of Professor Afolabi for the President’s Associates Teaching Excellence Awards at the University of Texas at Austin demonstrates his commitment to education through his substantial influence on students in addition to his numerous contributions to his field. This award honors educators who profoundly impact their students’ lives. Afolabi’s nomination is a remarkable achievement, especially for a Nigerian scholar in the diaspora.

Epilogue

Iwin said the firewood of the world

is for the ones who can take heart.

But your sacrifices for humanity

is a testament that everyone can gather it.

Your revolt against racism and

fight for social equality will only make

The world a better place in the universe

where insanity is treasured.

You are the change; you are the force

to regulate the abnormalities of this world

Alas! the insanity within

Must be stronger than the insanity beyond the boundaries.

Honor well deserved.

Lucidly put, concise and all encompassing. The success story of a scholar of global repute, Professor Niyi Afolabi, a polyglot, and a historiographer. A narrative put together by the classic biographer, the Enu-dun-ju-yo of our generation, Professor of Professors, Emeritus Professor Oloruntoyin Falola, and woven into a spicy evening pepperoni soup. Even a reluctant reader soon ends up gobbling down the dishlike texts that keep rolling on and on, in a seemingly endless gyre. Reading the piece takes the form of an excursion through a text material, the apparent series of academic conquests of a scholar of a rare and a celebration of his uncommon exploits by his research over the years, the historiography of the Yoruba Brazilian returnees versus the homeland Yoruba, among others interesting topicalities.

What a way to celebrate a colleague who’s about to earn another well deserved honor, an Award of acknowledgement of Prof Niyi Afolabi’s teaching skills and prowess. Thanks Emeritus Professor Toyin Falola, the Ojogbon Agba Pataki, Eegun Ologbojo, Ako Erinla a bori popo! More ink to your creative pen; and to Prof Niyi Afolabi, more wins and more stars to your Diadem. Cheers, my 2 Kobo. DAO

An eye-opener for me!

Ajepe aiye for our iconic Professors.