Toyin Falola

Distinguished Professor of Political Science, University of Pretoria

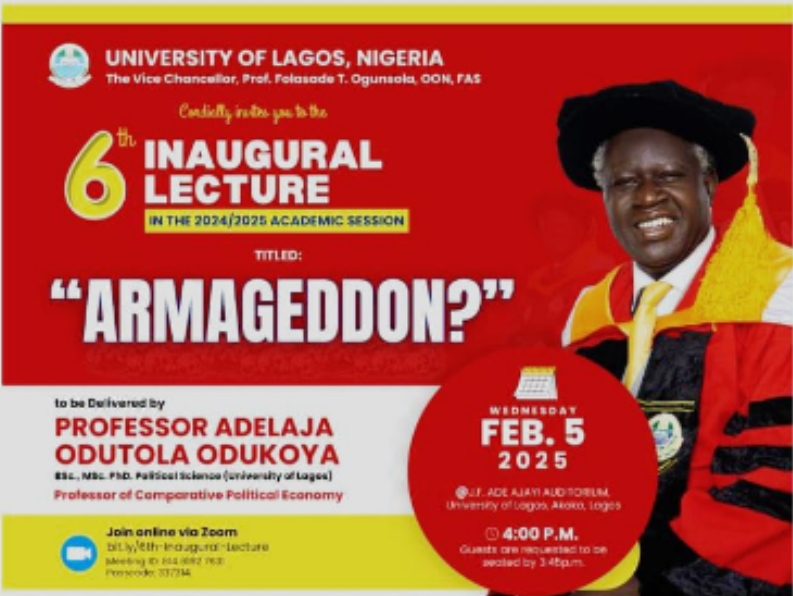

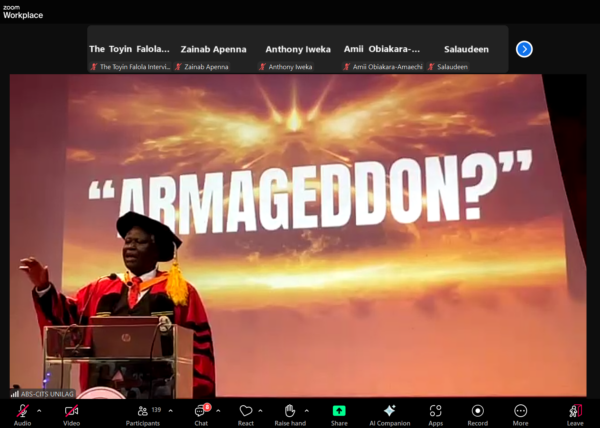

This is a reflection and takeaway from Professor Adelaja Odukoya’s Inaugural Lecture, “Armageddon,” delivered at the University of Lagos on February 5, 2025.

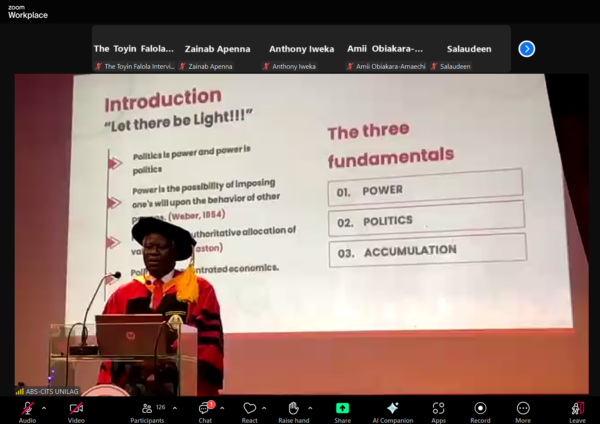

One thing remains constant throughout the vast span of human history: the distribution of power and resources continues to determine the course that civilizations take. Beginning with the biblical command, “Let there be light,” and continuing up to the frameworks of contemporary governance, power, and politics emerge as the two primary factors that shape human civilization. Considering the African context, this fact manifests itself with significant repercussions. The interaction between politics, power, and the accumulation of resources is at the core of the issues the continent faces regarding its growth. This highlights these forces’ key role in deciding societal situations’ outcomes.

The continent of Africa, considered the cradle of advanced civilizations and the place where humanity was born, is currently struggling with paradoxes that defy understanding. Even though the continent is home to large tracts of arable land, abundant natural resources, and an enormous cultural heritage, many of its inhabitants live in highly impoverished conditions. The dramatic contrast between abundance and deprivation is unsettling and instructive and should be considered. This, however, understood, sheds light on the historical causes of imperialism, exploitation, and structural injustices that have woven a complex web around Africa’s progress

In Africa, the history of external dominance and internal strife has cast a long shadow over the continent’s political and economic institutions. This shade has been cast for a considerable amount of time. Throughout its history, Africa has been subjected to unrelenting cycles of exploitation. These cycles began during the mercantile period, which was the time when the continent was integrated into the global capitalist system through the transatlantic slave trade. These cycles continued through the colonial and neocolonial eras as well.Because of this, not only has its progress been stifled, but it has also established patterns of dependency that continue to this day. The mechanisms of government, which were inherited from colonial control, were not designed to empower people but rather to extract them from them. Consequently, they continue to be fundamentally contradictory to the goals that the African people have set for themselves.

For example, Nigeria, which is frequently called the “giant of Africa.” This nation, blessed with an enormous number of natural resources and a rapidly growing population, exemplifies both the potential and the crisis the continent faces. Crippling governance challenges, rampant corruption, and systemic underdevelopment are all problems that are pervasive across Africa, and Nigeria’s struggles are a mirror of these concerns. Also prominent across Africa are widespread problems. Even though Nigeria is financially prosperous due to its oil industry, it has not been able to transform its enormous resources into tangible benefits for its populace. A cycle of poverty and inequality that threatens the very foundations of its society has been produced due to the misuse of governmental resources, which, combined with the domination of unproductive capital, has created this society.

A fundamental cause of this ailment is the intertwining of power and politics with the systems responsible for amassing resources. Historically, political authority in Nigeria, as well as throughout a significant portion of Africa, has been used as a tool for individual gain rather than for the benefit of the community. It has become an arena for primitive accumulation, where the spoils of governance are dispersed among a restricted few rather than serving as a stimulus for progress. If anything, the state has become an arena for primitive accumulation. A culture of impunity has been maintained because of this, in which public office is regarded not as a responsibility but as an opportunity for personal wealth.

The all-pervasive effect of external causes makes this grim reality even more difficult to deal with or comprehend. The global capitalist system, which is driven by the dominance of neoliberal economics, has contributed to the further marginalization of individuals in Africa. In many cases, the structural adjustment programs, trade liberalization, and other policy prescriptions that international financial institutions have enforced have further cemented dependency rather than developing independence. Due to their actions, the state’s ability has been diminished, local industries have been harmed, and debt payment has been prioritized over investments in development.

Conversely, the story of Africa is not one of unbridled, unmet hopelessness. One finds many instances of perseverance, creativity, and promise throughout the continent. Every region has these kinds of examples. From the historical successes of civilizations including Mali, Egypt, and Benin to the contemporary developments in technology, arts, and entrepreneurship, the legacy of Africa is a monument to the inventiveness of its people. On the other hand, these pockets of progress have to fight the more significant structural issues that are stifling their growth.

When the dichotomy of Africa’s wealth and poverty is examined through the prism of history, it becomes less confusing. Throughout the continent’s history of incorporation into the global capitalist system, the themes of plunder, exploitation, and marginalization have remained continuous. These historical currents, which date back to the mercantile and now reach up to the present day, provide crucial insights into the structural challenges that continue to impact the course that Africa’s progress will follow.

The mercantile era, which signaled the start of this system, was the moment when a forceful link between Africa and world capitalism was developed. Though it is sometimes romanticized as a chapter of human history that was unfortunate but necessary, the transatlantic slave trade was a purposeful act of violence that caused disturbances in African societies and economies. This incident resulted in a significantly lowered workforce for the nation and left behind a legacy of fragmentation and instability. Millions of physically competent people were taken from the continent under compulsion to reach this target. The mythology accompanying the ideas of racial superiority and cultural inferiority set the stage for later colonialism and economic supremacy of Africa.

Arguably, the most crucial era in the history of human exploitation in Africa was colonialism, a formal system of imperial rule and dominance. Between 1884 and 1885, the Berlin Conference took place, and a system of administration meant to extract resources was standardized. During this convention, the European countries divided the continent without considering the people or cultures already existing there. The economic plunder came from the colonial government, characterized by strict hierarchies and rules excluding particular groups of people. Infrastructure was developed to promote the export of raw commodities to imperial cities, not for the advantage of Africans. This was carried out to promote financial development. Indigenous knowledge systems were undermined, cultural relics were taken, and local businesses were turned to further foreign power interests. All these activities were carried out to forward the objectives of such powers.

The legacy of colonialism is still evident in the shape of governments created artificially and whose borders violate the linguistic, cultural, and ethnic reality of their people. These governments represent a legacy of colonialism expressed. Apart from fueling internal conflicts, these arbitrary limits have made creating coherent national identities that complement one another more challenging. The colonial government set a model for government whereby the well-being of foreign interests was valued above the welfare of the home population since it gave extraction top priority above development. The concentration on extraction of the colonial government helped to create this precedent. This tendency has continued from the moment of independence until now.

The independence movements raging throughout Africa in the middle of the 20th century brought about aspirations of a fresh beginning. Significant leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, and Amílcar Cabral once envisioned a continent free from the constraints of empire. Conversely, the issues resulting from neocolonialism soon superseded the thrill of freedom from colonial control. The patterns of reliance did not change since African states kept depending on markets, technology, and foreign aid. This made the patterns able to stay unaltered. At the moment, the West-dominated global economic system insisted that everything remained the same. This was done to guarantee that Africa’s function as a market for completed goods and source of raw resources stayed unaltered.

A domestic aristocracy emerged when the nation gained its freedom, reflecting their colonial forebears’ predatory nature. This elite so developed throughout the era following independence. Many post-colonial elites did not destroy the repressive systems they had created; instead, they reused the repressive institutions they had built for their financial benefit. The state evolved into a site for gathering primitive products at the time when resources were moved from the progress of the public to the enrichment of individuals. It became clear that corrupt actions were arising from government policies growing more and more detached from the needs of the people.

During the 1980s and 1990s, structural adjustment programs (SAPs) were primarily implemented by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These initiatives, notwithstanding their best efforts, kept the economic problems of Africa worsening. Regarding these initiatives—which were enforced as requirements for financial aid— privatization, trade liberalization, and fiscal austerity were the three most essential elements imposed. Though their intended use was to promote stability and economic growth, their influence on African countries was disastrous. This was the case even with development involved. Public services fell apart, businesses collapsed, and the divide between many groups of people grew as a result. Furthermore, the situation is aggravated by the acceptance of SAPs, which has not only neglected the fundamental issues of Africa’s economic crisis but also strengthened the continent’s reliance on businesses not native to Africa.

Given their frequency, the historical tendencies observed in Nigeria are rather obvious. Experience under colonial power left behind by the nation a legacy of centralized government and economic reliance on a single resource—oil. The country carried behind it this heritage. Policymakers have decided to keep a rentier system advantageous for a small elite rather than diversifying the economy and promoting inclusive development during the post-independence era. Hailed as a necessary corrective by its designers, the Structural Adjustment Program caused further damage to the economy during the 1980s, resulting in great suffering and disillusionment among the people.

Given the combined impact of these historical events, a continent is presently facing structural problems transcending the actions or policies of individual governments. These difficulties arise from the influence of several historical factors. A vicious circle has been created inside the company from the interrelated legacies of exploitation, dependency, and poor management, stifling development and compromising the hopes of millions of people. The organization has built this loop out of necessity. Still, history is not the same as fate. Though it offers a dismal account of Africa’s problems, the past also provides education opportunities and can impart knowledge that would enable one to recover agency. Strong refute to the theme of pessimism are African civilizations’ tenacity, the rich cultural legacy of African people, and the unrealized potential of African people. The fact that African people have always been strong helps to highlight these refutes. The challenge that has to be conquered to remove the long-standing structural impediment preventing the continent’s growth is entirely using these resources.

There is a clear relationship between power dynamics and the challenges Africa is going through now. Utilizing the interdependence of these elements, the structural flaws preventing the continent’s development come to light. Fundamentally, these issues stem from the state’s contradictory posture—an institution necessary for development yet often used as an instrument of exploitation via its policies. Every society uses the state to organize communal life, manage resources, and preserve security and order. Its efficiency, therefore, depends on its ability to operate autonomously and in a way that promotes inclusion. However, the African state was not meant to allow autonomy or inclusion in its governance systems based on its colonial past. Conversely, it was a means of extraction, giving imperial powers’ interests top priority above the well-being of the local population. Even if this legacy has endured, the state’s power to carry out its developmental role has been compromised.

Once the continent gained its freedom, the state became the main forum for conflicts about authority. The elites who took over government often saw the state as a means of personal enrichment rather than a public service forum. This approach produced a predatory state whereby access to power was equated with access to riches. Only a few people benefited from office, so the majority was disconnected from the governance procedures, and inequality was sustained.

The loss of institutional skills adds still another element influencing this governance challenge. Effective government depends critically on institutions’ capacity to resolve disputes, uphold the rule of law, and provide public goods. These establishments ought to be open to public criticism and be credible. Notwithstanding this, decades of bad administration and political party interference have eroded the institutions of many African governments. Instead of driving forward, bureaucracies have become bloated and useless. Given its regular exposure to political interference, the court finds it challenging to build public confidence. Despite their supposed duty to defend democracy, electoral commissions sometimes become battlefields for claims of fraud and conflicts.

It is also crucial to underline that the crisis in governance transcends the home front. Moreover, the place of Africa in the world system limits the agency of its countries even more. International financial institutions, multinational companies, and governments from surrounding nations significantly impact African policy formulation. The influence from outside sources often compromises the national sovereignty and skews the development priorities. Regarding structural adjustment projects, for instance, outside players used these initiatives to modify African nations’ governance structures rather than only financial ones. As a result, policies placed market efficiency above social welfare, aggravating existing inequalities and widening social divisions.

Under the framework of this conversation, democracy has sometimes been limited to the level of procedural guidelines. Though they are vital, elections have become shallow rituals devoid of purpose. Often, the underlying reason for indifference—which results in poor voter turnout—is the lack of faith people have in the political system. Many voters view elections as spectacles in which power is distributed among the same elite coalitions, not as a means of exercising control over government. This cynicism reflects the greater widespread alienation from the government, a gap that causes unrest and, in some cases, insurgency.

The increasing frequency of authoritarian impulses in many African countries still offers more evidence of the unstable character of the government. Military coups were once thought of as relics from the past, yet, in recent years, they have resurfaced in response to what are believed to be shortcomings in civilian government. These events expose the limitations of controlling ideologies that support power consolidation over variety and responsibility.

Notwithstanding the challenges faced, Africa’s governance condition is not entirely bleak. Every continent has examples of creativity and tenacity shown there. Rwanda’s post-genocide recovery—not without controversy—indicates that strategic governance has the power to be a driving agent behind progress. The somewhat calm change to democracy Ghana has gone through emphasizes the significance of solid institutions and constant political will. Though different, these examples provide essential insights to help us rethink the African government.

To move on with the route ahead, it is vital to rethink the state and its role in society. Governance must shift from being a control exercise to becoming a practice of empowerment to be effective. Not only is it required to correct the structural defects within the state, but it is also necessary to build a culture that emphasizes accountability and involvement before this can be accomplished. Citizens should not be considered subjects to be governed; instead, they should be regarded as stakeholders in the governance process. This is an essential requirement. During a transformation of this magnitude, it is necessary to have daring leadership, formulate policies that emphasize inclusivity, and be committed to justice and equity.

The inability to diversify economies is another aspect that adds to these issues. There is a correlation between dependence on resources and the development of other businesses, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which can build a more stable platform for growth. As an illustration, Nigeria used to be a world leader in agricultural exports, and its groundnuts, cocoa, and palm oil were in great demand during that period. Agricultural productivity and food security suffered due to the oil boom, diverting attention and resources from agriculture. This led to a drop in both production and food security. The fact that the nation currently needs to import a sizeable chunk of its food supply serves as a clear reminder of the dangers that might arise from excessive reliance on a single resource.

Despite this, Africa possesses a wealth of resources, which suggests there should be opportunities for change. Botswana and Namibia are two examples of countries that have demonstrated that effective governance and strategic planning can be utilized to make the most of abundant resources for the goal of development. Both of these countries have shown that this is possible. Additionally, Botswana has developed a comprehensive social and economic infrastructure by exploiting its diamond business. This has been a significant accomplishment for the country. The fact that its government has been so adamant about striking equitable revenue-sharing arrangements with multinational companies has made it feasible for its population to realize the benefits of the immense resource wealth that the country possesses.

These successful resource management cases teach us how crucial it is to be honest, own responsibility, and have long-term objectives. Through this, they demonstrate the need for African governments to reclaim control over the allocation of resources. Local institutions must be strengthened to ensure that trade and business are carried out more equitably, and global economic system improvements must be pushed for. The accumulation issue in Africa calls for reevaluating African economic objectives. Investing in industrialization and value addition will help to make resources more than just commodities to be sold. Raw material processing in African nations could provide employment, increase creativity, and help to retain more money in national budgets. On the other hand, large expenditures in sectors including infrastructure, technology, and education—which have not received significant funding in the past—are required to bring about this transition.

Africa is in a time when danger as well as opportunity abound. We need more than simply little, transient modifications or reforms if we are to advance. Reevaluating power, government, and economic institutions from the ground up will help us to do this. A strong dedication to justice, sustainability, and equality will help support this. Deeply ingrained in history, the issues the continent faces are influenced by power relations and maintained alive by structural inequality. We must have an intense and all-encompassing vision for transformation to address these issues. The most crucial aspect of this concept is that it will release African people. For far too long, African administration has been overly top-down. Elite decision-makers who lack knowledge of the hardships the people experience make decisions. If Africa is to be transformed, participatory government has to be the priority. Under this type of government, individuals have a stake in the future and contribute to making it a reality. We have to inspire an attitude of openness and responsibility if we are to meet this target. This will guarantee that governments serve the people’s best interests rather than those of large corporations.

A population that is informed, gifted, and capable of pushing for fresh ideas and holding leaders accountable depends on a strong educational system. Conversely, many African nations have underfunded education, so the next generations of young people are unprepared to operate in a fast-changing world economy. More money is needed to arrest this tendency, and educational programs must also be refocused to include more cultural relevance, critical thinking, and digital skills. By arming people with the knowledge and confidence they need to oppose injustice and advocate change, education should be a means of liberation.

Another crucial component of Africa’s destiny is the reformation of its economy. Proper management of the resources on the continent might support industrialization and diversification. The nation must do more than only export essential goods if it is to do this. It must create businesses that enhance the value of these products. Investing in infrastructure, technology, and human capital during economic development will help African nations establish robust economies that provide employment and reduce their dependence on erratic world markets. Simultaneously, a concentrated effort is required to resolve the issues that have been influencing the continent for many years. Two of these include eliminating corruption, which costs money and time away from development, and ensuring that every person gains personally from economic success. Laws encouraging development that benefits everyone must exist to create a more equitable and stable society. These policies include progressive taxes, social safety nets, and equitable land distribution.

One should also consider how issues in Africa impact the rest of the globe. The continent reached where it is currently in the world order using long-standing exploitation and pushing to the margins of society. Countries must cooperate strategically with international organizations, support policies that promote fair trade, and expose the unethical behavior of multinational businesses if they are to regain control of the world scene. Africa’s nations must cooperate to safeguard their interests. Drawing on their shared past and resources will help them to negotiate from a strong position.

Rich in languages, customs, philosophy, and history, Africa provides a wealth of knowledge and the will to press on. Reconnecting with this past can help one develop pride and identity, combating the emotions of self-doubt and loneliness left behind by globalization and colonialism. If Africa appreciates traditional knowledge and modern science, it may forge a mainly African road to riches. This kind of living would be based on the continent’s past and receptive to the future.

Africa’s development relies on the people who live there, even when all the policies and actions are taken. Past challenges have imparted valuable lessons and demonstrated the need to work together ahead of time and tenaciously continue. The several countries and cultures that comprise the continent must see that their fates are entwined and figure out how to cooperate.

The things Africa has to give are less significant than the issues it confronts now. The power of its people, the diversity of its cultures, and the volume of its resources define some of the most crucial factors determining a brighter future. If Africa addresses the issues impeding its development and embraces a vision of empowerment and sustainability, it will be a shining example of human triumph, overcoming its problems. This journey is neither swift nor simple in any sense. We must be courageous, inventive, and always driven to succeed. Still, this journey is worth traveling since it could lead to a time when the riches of Africa would be recognized as evidence of the strength and creativity of its people rather than as a contradiction.