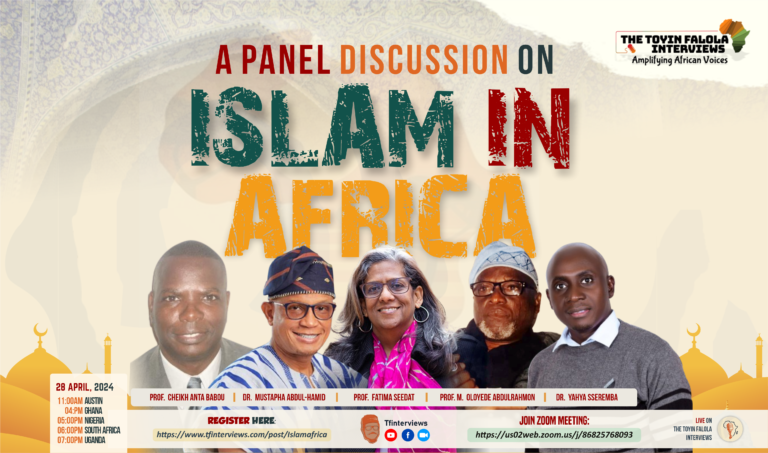

This is the second interview report with a panel of African scholars on Islam in Africa

Religions have been a vital part of the existence, evolution, and development of human societies for millennia — from what is now commonly known as “pagan worship” among contemporary religionists to the most popular forms of religion as the world knows it today. Several religions have, at some point in time, been in the coveted spots that Islam and Christianity occupy in today’s world. Maybe they will cede those spots to some other religions centuries or millennia from now, and maybe they won’t. In all of this, certainly, humans have always found the need to worship and submit to a higher authority, as much as if it is a core need like eating, sleeping, or taking water.

Source: Muslimink

Similarly, religions have also survived successfully over thousands of years because they experience evolution and development, and scholarship has proven to be one of the ways to advance the evolution and sustainability of religions. For each of the world’s most popular religions, some people have dedicated their lives to study and scholarship. These people’s interpretations and expositions help others better understand and grow in the practice of their religion. For thousands of years, religion has also proved to be one of the concepts humans are most dedicated to, thereby making it an intriguing field worthy of further research and study. It is the scholarship that birthed the last Toyin Falola Interviews in Africa, where the focus was on exploring scholastic religious views and opinions.

In Professor Cheikh Anta Babou’s view, the African Islamic identity is a discursive one, neither diluted in the global Islamic ummah nor confined solely to Islam, meaning the African Islamic identity regroups identities that reflect lived Islam unlike Orientalist Islam — which is largely defined as a set of unchanging morals, values, and ideas confined to a book as its way of affecting reality — the African Islamic identity reflects a form of Islam people live; a form of Islam that is studied and researched. African Islam responds to the African people’s existential and spiritual needs. This ultimately means that Islam has a rich history in Africa, given that Africa’s history is rich and diverse.

Source: Learnsquran

Before the advent of Western education in Africa, there was communal education, although not strictly structured and formal. There was also oriental education, which gained further structure through the establishment of Islamic schools across several African states. When Western formal education was introduced, and as it continued to gain popularity as the bridge between citizens of the continent and the world at large, other forms of education that had existed on the continent before it began to witness subjugation and relegation, especially from the views of occidental historians documenting Africa and Africans through writing. The spread of occidental views and culture, no thanks to their conquests and colonization of African states, meant that their form of expression and education gained widespread acceptability as the only recognized form of education.

In his recent research endeavors, Dr. Yahya Sseremba has focused on the production of Islamic truth in his home country, Uganda. This focus rests on the belief that the interpretation of Islam in Islamic schools in East Africa is wrong and occidentally influenced. His research has also explored the age-long debate on the conferment of authority on Islamic scholars and religious leaders, specifically, what qualifies one to define what is Islamic and what is not. What are the criteria for making such a claim? Who gets to make the claim?

Over the years, the Islamic education system in Uganda has faced interventions and influences from Western countries, especially the Uganda-US contention on the content of the Islamic education curriculum in the country. This influence, whose focus has been on defining good and bad Islam, is problematic for the Ugandan Muslim population, whose experiences should be the determinant of what is good and what is bad within the context of their religion, as against the definition being passed down by a secular state.

Source: Worldcrunch

Since religion forms an integral part of organized society as we have always known it, the colonial character of modern power — which continues to heavily influence the state and society — maintains its influence on culture, ethnicity, religion, and other elements of state and society. “Tribe,” a colonial terminology used to politicize ethnicity and allocate local resources and rights, has continued to stay relevant long after the colonial era. Decades after independence, several African states still wallow in ethnic wars and disagreements, such as the Rwandan genocide, the ethnocide and genocide in Sudan, and the Congo wars, among others.

Dr. Ssembaya’s comments on the similarities between the creation of “tribal” subjects and colonial subjects in colonial and post-colonial Uganda lend credence to the establishment of religion as an integral fiber of evolutionary society. The two most popular external religions in Africa have served political will — conquest, education and commerce, expansion, law and order, and societal development.

Source: Quora

Post-colonial Uganda’s experience of the politicization of Islam escalated under the Idi Amin regime, where the sect-based practicing of Islam was eliminated in favor of a state-wide, government-dictated management of Islamic practices in the country. Under Idi Amin’s government, the state took over the role of governing Muslims and defining what Islam was and was not through the Ugandan Muslim Supreme Council, thereby relegating the role of religious leaders. Since Idi Amin’s efforts to unify Ugandan Muslims and their belief in a state-controlled religious body — which expectedly lost relevance quickly after his death — there have been some other attempts at bringing Islam under widespread state domination in Uganda. The first of the three has been the attempt by feminists with a view to eliminate the Muslim domain in general and bring Muslim affairs under the civil governance administered directly by the Central State.There has also been a persistent petition by the Muslim faithful to the state, calling for the recognition and institutionalization of Islamic law in the Ugandan state. While the success of this petition would mean the legitimization of Islamic law in the Ugandan state, the other side of the petition that Muslim societies might not have considered is the empowerment of the state to regulate how Islamic law in the state can and cannot define Islam. It is an indirect way of eliminating the bifurcated nature of the post-colonial Ugandan state.

Finally, the United States of America has also weighed in on the conversation through its championing of counter-extremism campaigns. These campaigns have focused on Islamic schools in Uganda and Islamic education, considering them as the breeding ground for extremist views and launching interventions such as the unification of the diverse and sect-based curriculums of madrassahs (Islamic schools) into one moderated curriculum. While this move is being claimed to help ensure everyone is on the same page, and extremist views are easily combatted, it takes away the authority of religious leaders to define what Islam is and what it is not as the custodians and interpreters of the religion. This would also empower the state to regulate Islamic education, determine who can or cannot become an Islamic teacher, and vet the curriculum, leaving the state with the power to define the acceptable tenets of the religion.

Source: Islamestic

Dr. Ssembaya’s notable point on the contextualization of violence vis-a-vis secular and religious actors is worthy of further analysis. According to him, the violence of secular actors is contextualized within environmental, psychological, and social factors. The violence of any religious actor is immediately blamed on Islam, although such an actor could well have interacted with similar social, environmental, and psychological elements as a secular actor. The presence of Islam is never considered a coincidence when interpreting extremist behavior or actions. This leaves room for considerations on whether the fears are truly founded or are solely based on Islamophobia.

I am always thought about this, appreciate it for putting up.