Toyin Falola

Not merely a writer, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was a force that changed how Africa saw itself and how the world saw the continent’s pursuit of intellectual and cultural sovereignty. May 28, 2025, marked the day of his passing to the great beyond, but as seen in his life spanning over nine decades, literature can be both a mirror and a hammer, reflecting society’s truths and a tool to demolish its illusions. His life was a testament to the power of literature to effect change and sustain such changes. From the moment his debut book, Weep Not, Child (1964), was published and available to the public, his voice was identified as one that refused to whitewash history or shy away from the wounds of colonialism. Still, his legacy goes beyond the written form. Starting with a family of peasants in Kamiriithu and ending in a worldwide symbol of resistance, Ngũgĩ’s career was defined by an unflinching belief that language is not only a tool for communication but also the fundamental core of a people’s identity.

Early in life, he lived in the conflict of a society split between colonist schools and oral traditions from his Gikuyu village. Unlike his contemporaries, who often wrote in English to draw readers from around the world, Ngũgĩ took a crucial step in the 1970s by writing in Gikuyu, a move that was a form of resistance. He believed that colonial languages were agents of erasure, separating generations from their cultural foundations rather than neutral tools. He once said, “To choose to write in Gikuyu was to choose the people’s side.” This choice cost him his comfort, independence, and even his praise. He was imprisoned without trial in 1978 for co-writing a politically delicate drama in Gikuyu called Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”). But, rather than break him, this conduct simply helped to increase his will to rebel against the government.

Conversely, his imprisonment turned into a furnace. On pieces of toilet paper, he scribbled the first modern novel written in Gikuyu, “Devil on the Cross,” while confined in a cell. In a symbolic sense, the gesture stood for a rejection to let tyranny silence the stories of people who are excluded. The book’s symbolic critique of capitalism and neocolonialism, which resonated far beyond Kenya’s boundaries, solidified his reputation as a writer who handled words like a sword, demonstrating that an African language could carry the weight of modern critique as effectively as any European tongue. His later works, especially Decolonizing the Mind (1986), confirmed his philosophy into a global manifesto and exhorted not just African elites but the whole postcolonial world to question the residual hold of linguistic imperialism.

Ngũgĩ’s academic discipline matched his dedication to reviving local culture. His efforts, such as the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, exemplified his criticism of the ivory tower approach among academics. He insisted that art had to come from the soil and sufferings of the ordinary people. Among the locals working together to produce plays that challenged the seizure of land and the disparities in socioeconomic classes, the separation between the artist and the audience was blurring. This participatory method was both political and artistic, serving as a rejection of top-down narratives that excluded the views of people who were oppressed.

This obsession with writing in Gikuyu by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was about memory, power, and the freedom to create one’s own story, not just language. The erasure of indigenous languages evolved into a strategy meant to disconnect people from their collective imaginations, ideas, and histories. Often referring to colonialism as a war of conscience as much as of conquest, he said, “A language carries the soul of a people,” he remarked in Decolonizing the Mind, “and to kill a language is to kill a culture.” This philosophy drove him to battle with colonial rulers as well as post-independence elites who considered English as a pragmatic link to global modernity. Conversely, Ngũgĩ saw such pragmatism as a kind of betrayal. He maintained that the acceptance of colonial languages without critical investigation helped to uphold a hierarchy in which African epistemologies were considered inferior, and their oral traditions were dismissed as folklore rather than being recognized as valid sources of knowledge.

His linguistic activism set off intense debates. Many attacked him for romanticizing regional languages while also downplaying the reality of living in a globalized world. Although Gikuyu is a language primarily spoken in Kenya, others questioned whether writing in Gikuyu could truly reach the audiences he was aiming to influence. Ngũgĩ’s answer was resolute: rather than passively following the frameworks set by others, one must recover the means of expression if one is to gain true liberation. He referenced historical events, such as the Soviet Union’s encouragement of Russia among minority republics and the assimilation operations in French colonies, to illustrate how language supremacy has always been a fundamental component of imperial authority. Choosing Gikuyu as his language of choice meant he was reversing this rationale. He claimed that every language has a universe of ideas capable of expressing complex concepts, from political theory to quantum physics, without resorting to borrowing from colonial tongues.

This idea was met with resistance almost immediately. After it initially aired in 1982, the condemnation of class exploitation and land inequalities offered in Ngaahika Ndeenda enraged the Kenyan ruling elite. They considered the show as a challenge to their authority. The grassroots appeal of the drama, which relied on audience participation and was performed in towns devoid of props, alarmed the authorities. Ngũgĩ was taken into custody and sent to prison; not too long later, the Kamiriithu theatre project was shelved. On the other side, the crackdown helped him to spread his message. While he was imprisoned, his will grew stronger. Later, he argued that jails were “universities of the oppressed,” places where silence encouraged one to pay closer attention to the echoes of history.

Between 1982 and 2004, Ngũgĩ went into self-imposed exile due to threats and censorship on his life and work, a period that marked a retreat and a development of his worldwide impact. From Yale to the University of California, Irvine, where he mentored a new generation of intellectuals, he taught in several colleges in the United States. He maintained his spirit during his stay in the American academic community despite being far from his home country. His lessons were passionate cries to arms, in which he urged students to see language as a battlefield for the preservation of cultural traditions rather than as dry intellectual exercises. Two of the ways he stayed in touch with Kamiriithu even after he had left Kenya were the Gikuyu proverbs he included in his lectures and his determination that “the fight for linguistic justice is never confined to borders.” This exile came with a cost, though; he described it as “cultural homesickness,” his alienation from his hometown, and his incapacity to travel the nation that had produced his writings. This was a craving for the location as much as for the rhythms of life that one’s mother tongue could fairly express.

His return to Kenya in 2004 was marked by excitement, albeit with a hint of caution. Though the country he had fiercely attacked had experienced significant changes, the same problems of corruption, injustice, and marginalization of indigenous voices persisted. He continued writing and eventually released “Wizard of the Crow” (2006). This satirical masterpiece mocked African leaders and global business, demonstrating that his years of experience had not diminished his sharpness. Written in Gikuyu and subsequently translated into English, the book became a monument to his lifetime experiment, proving that an African language could sustain the weight of sophisticated storytelling without surrendering to colonial norms. Critics discussed its merits, but few could deny its chutzpah; it was a literary Jenga game in which humor and myth collided to show the foolishness of authority.

Ngũgĩ remained a topic of debate throughout. Others contended that multilingualism, not monolingual opposition, was the destiny of postcolonial countries, thereby criticizing his linguistic purism as impractical. Although some hailed him as a visionary, others called him impractical. Although he acknowledged these complaints, he remained true and drew comparisons between the struggle against apartheid and the fight for language. He said once, “You do not negotiate with a thief who has stolen your memory.” In his last years, his ideas attracted increasing interest, particularly among young campaigners striving to preserve African languages under threat from globalization. By 2024, his influence was indisputable, as he had successfully bridged the gap between the oral traditions of his ancestors and the urgent needs of a digital and interconnected society.

After the passing of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, an era comes to an end. He leaves behind the idea that language is never neutral and that every word spoken or written is a decision between submission and opposition. If you destroy the stories of a people, what is left of their souls? He asked this question several decades ago, and it still haunts the globe today.

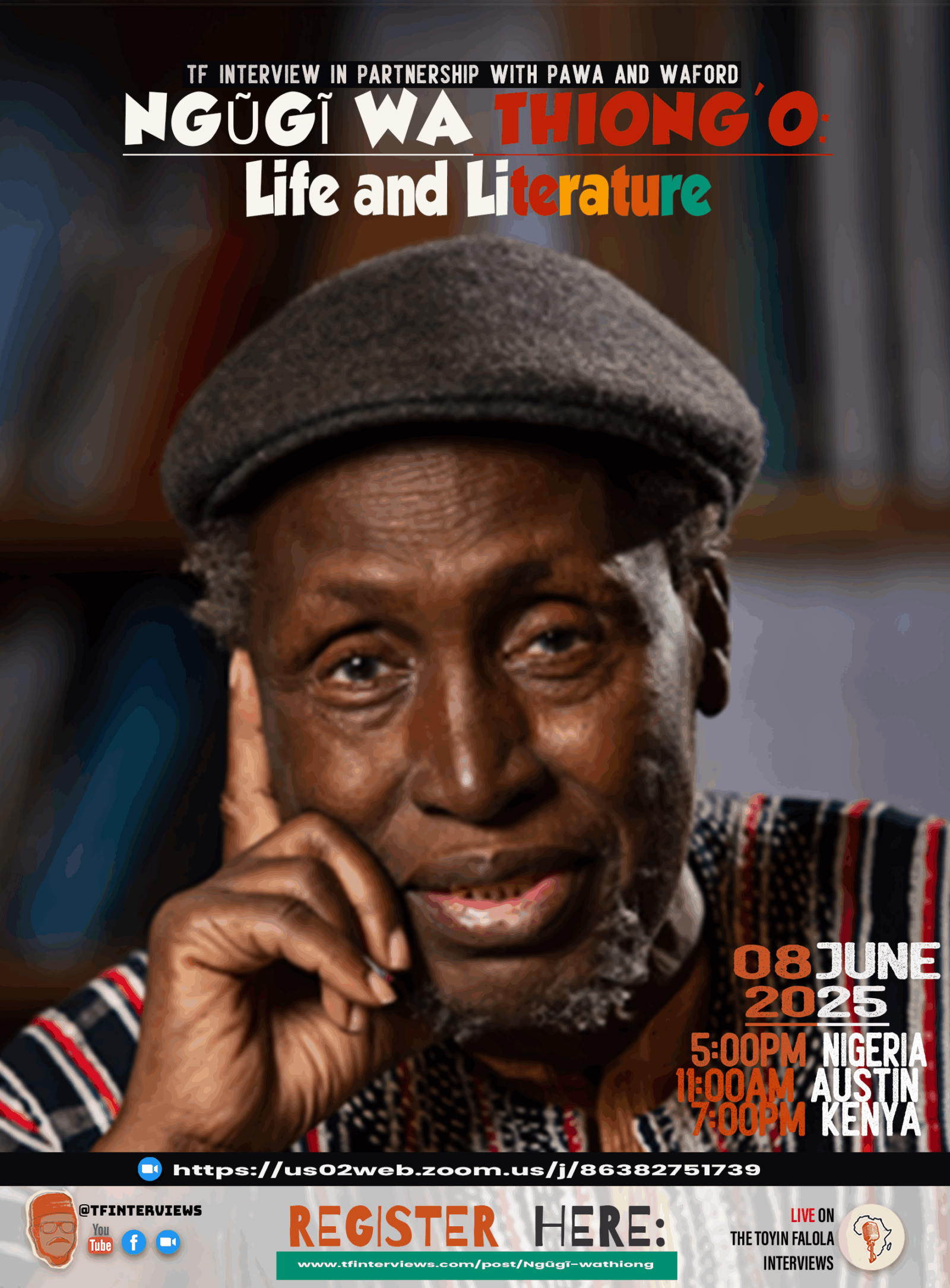

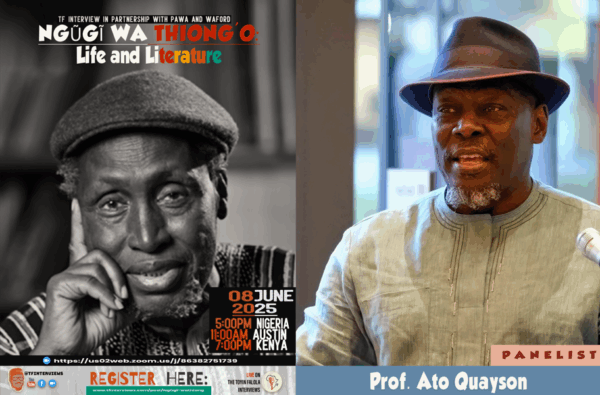

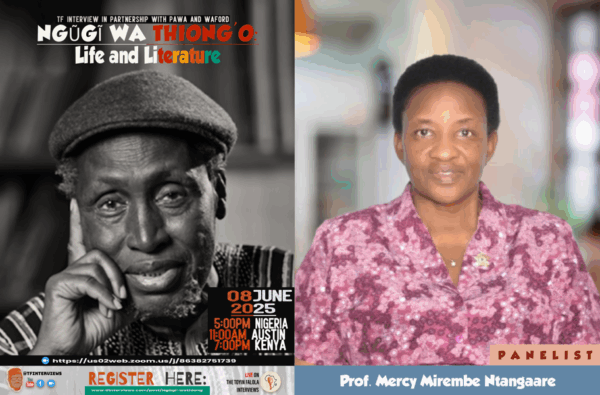

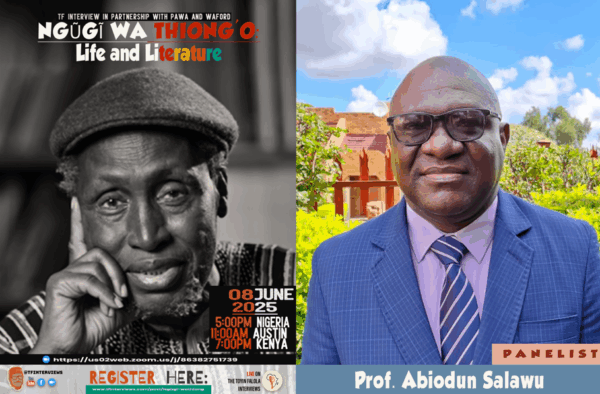

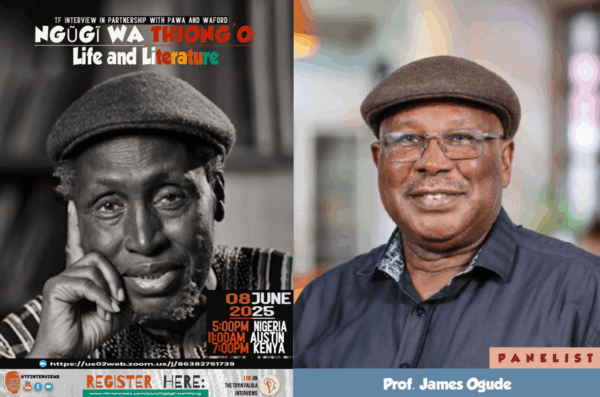

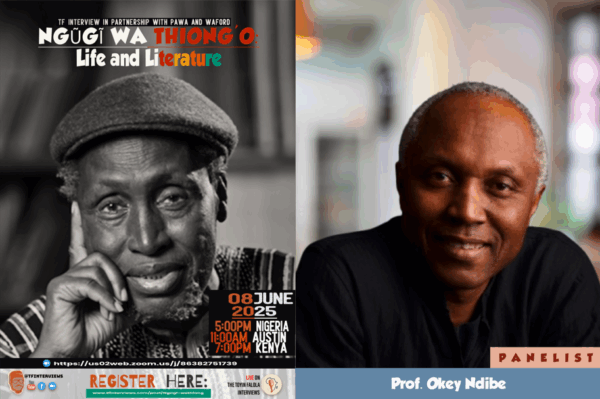

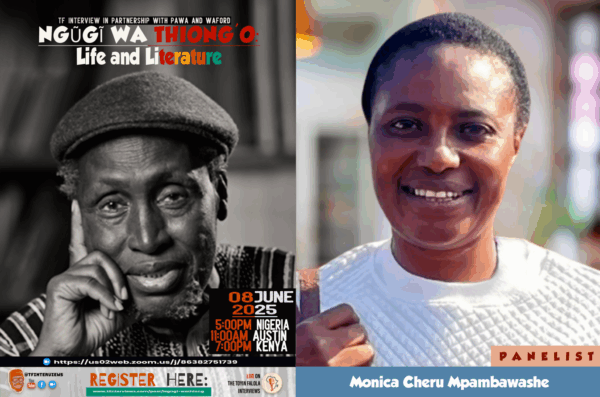

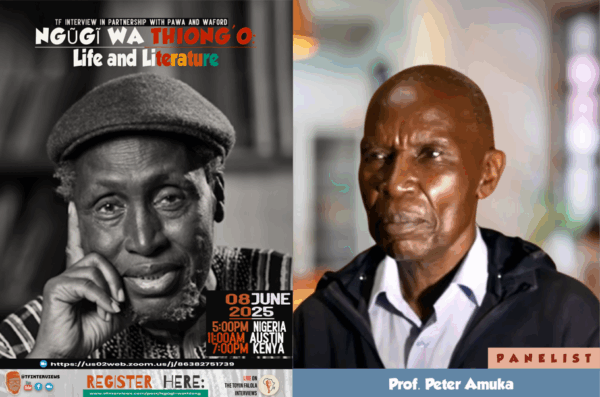

Please join us for a panel discussion featuring our distinguished panelists, comprising scholars from various African countries, who will share their expertise on “Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: Life and Literature.”

Sunday, June 8, 2025

5 PM Nigeria

11 AM Austin

7 PM Kenya

Register Here:

https://www.tfinterviews.com/post/ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9-wa-thiong-o

Join Via Zoom: