Toyin Falola

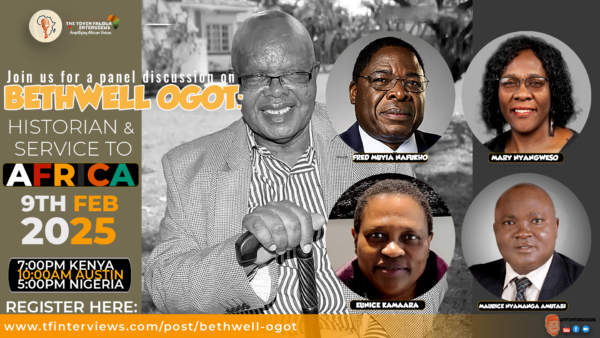

I went in search of Professor Ogot, as I looked for Professors Jacob Ade Ajayi and Adu Boahen. I traveled to Kenya and Ghana to meet both great men. I published the collected essays of the three of them with Africa World Press. With Atieno Odhiambo, I co-edited The Challenges of History and Leadership in Africa: The Essays of Bethwell Allan Ogot. We met several times—in France, the United States, Kenya, Tanzania, and in many unforgettable moments. I respected his elderly status, and I let him do the talking. In Houston, he was hosted by Rice University, and I drove down to have a moment with him. A great library, his store house of knowledge had depth and breath. Never a time would I be with Professor Maurice Amutabi that we will never talk about Professor Ogot and members of his generation. He survived them all. They are all gone, but the history of the moment remains with us.

Life’s deepest lessons often reveal themselves with time, as human nature inclines us to grow in knowledge and understanding as we age. One of these enduring truths is the inevitability of endings—no matter how deeply we cherish an idea, an individual, or an experience, everything must eventually come to an end. But instead of worrying ourselves sick over the inevitability of death, we should take lesson from the deeper philosophy underpinning this inevitable phenomenon: our time in this world is finite, and within that limited span, we must strive to leave a lasting impact. The human family is, therefore, expected to utilize their limited time to create maximum impact so that they would leave a mark after they have gone. Life continually reminds us that no matter how virtuous or accomplished we are, nature does not grant special exemptions. Mortality is an unyielding constant; we are all subject to its call. It is in this light that we reflect on the passing of Professor Bethwell Ogot, a renowned Kenyan and pioneer historian of Africa, who has now gone to join the ancestors. Upon a reflection on the life of this now fallen iconic figure, it is safe to say that he made irreplaceable marks in the history book.

It is on this note that I commiserate with the body of African intellectuals who would sorely feel the vacuum created by the exit of this outstanding individual in the African intellectual space. I extend my deepest sympathies to this body of scholars and thinkers who will feel the weight of his absence. Our grief is not merely personal but collective — borne not just of sorrow but of the awareness that the loss of such a major figure leaves a void in our shared pursuit of knowledge and progress, which will continue to be felt by us the living. Professor Ogot was not just a member of an African intellectual family but a revolutionary force.

Generally, scholars of African origin born during the heydays of colonialism were destined to make unique contributions—ones that many might not have fully grasped the consequences. They belonged to a generation that witnessed and endured the systematic dehumanization of both their identity and intellect. It was a time when they were forced to internalize foreign ideologies that stood in stark contradiction to their indigenous ways of knowing. As a result, they were exposed to dangerous and detrimental learning content, which ultimately stripped them of capacity for broad, independent reasoning. This reality or awareness reinforces a critical truth: colonized Africans could not expand their intellectual horizons solely through Western educational frameworks. The colonial system conditioned them to engage with knowledge from a singular, imposed perspective, limiting their ability to conceive ideas beyond that rigid structure.

Professor Ogot was born into this dehumanizing reality: when colonizers were actively expanding their reigns in Africa, consolidating their imperial status by taking charge of many African countries’ political and economic systems. Even when he had no idea that he would be a historian of international stature, he conformed himself and learned in different ways. Although the Western education system was enforced in the academic environment, those of his period also had the opportunities to learn from their parents and absorb knowledge preserved through generations or oral medium and transferred to them using the same platform. This became the foundation of their clear resolve against external aggressors. Armed with both intellectual depth and historical awareness, they stood as the defenders of African identity and autonomy against these external forces that sought to exploit them for material gain.

One of the first points of his campaign and advocacy for epistemic democracy is that African knowledge centers and Indigenous epistemologies should not be sacrificed on the altar of epistemic oppression because they were assumed to be inferior. He was one individual who mastered the art of knowledge transfer bequeathed to him through his lineage and other social agencies of socialization and knowledge exchange. Given his reality and background, Professor Ogot was not easily swayed by arguments that sought to delegitimize African ways of knowing.

Professor Ogot was one of the prominent African historians who amplified African historiography by stating that the universal pattern of handing down historical information contradicts and even undermines those available in their continent. This is underscored by the awareness that the assimilation of Western-derived history poses a very grave danger to the cognitive evolution of the colonized people. If anything, the amplification of European history in Africa and to Africans has the potential to erase all the great things that the African forebears have achieved. It cannot be overemphasized that Africans would benefit tremendously only when they use their history to build or develop their younger ones. The underlying reason for the projection of African historiography is that it would provide a more nuanced and balanced approach to the history available in Western-based schools. It did not take Ogot and scholars like him long to recognize that the relentless promotion of Western history was not merely an academic preference but a strategic tool for reshaping African minds in ways that served external interests.

After successfully making a case for African historiography, Professor Ogot exposed the underhanded consequences of colonialism and how that sacrilegious experience had contributed to the desecration of the African past and then the deceleration of African progress. If anything, Ogot ensured that the adverse problems associated with colonialism were highlighted in such a way that Africans, and potentially other ex-colonies, would understand the operations of colonial politics and how they would be used in the future for familiar reasons. Ogot stressed in many of his works that colonialism was a cancer to African economic development. This conclusion he arrived at following his realization that the extractive policies imposed on the African people were meant to sabotage their possibility of economic initiatives.

It is a well-known fact that when people are deprived of economic power, they often find themselves in a state of disarray, unable to make independent decisions or shape their destinies within their communities. It cannot be overlooked how the indiscriminate extraction of African natural resources contributed to reducing their economic opportunities and values, which ordinarily should be under their control. The devastation extended beyond just financial ruin; history has shown that when a people’s economic foundations are dismantled, their political systems inevitably become a target—often weakened and manipulated to the point of near irreparability. The erosion of economic autonomy, therefore, was not just an economic setback but a deliberate strategy to undermine Africa’s self-determination. In essence, Professor Ogot performed excellently in revealing the dangers of imperialists.

All these were done simultaneously so that he could make a profound mark in the intellectual community of the African people. No one familiar with Professor Ogot would disagree with the conclusion that he was dedicated and selfless, especially regarding issues that he considered essential. The problem of African identity and culture is a central theme in the writings of this once-in-a-lifetime intellectual.

He advocated for a lifestyle of Africans that would principally elevate their original identity. He was a staunch believer in the philosophy that people exist and would continue to, only when they take the issue of their identity very seriously. Numerous lectures and countless publications credited to this precious mind are available today, where he projected the fundamentals of the African identity. He has always intoned that promoting such an idea would automatically yield the opportunity to make them popular or known in the general scheme of things. His intellectual productions revealed the African perspectives on general topics. He had a special preference for African culture and made no pretense about making local practices to be embraced across the continent. He was not merely an advocate of African heritage—he was a driving force behind its intellectual elevation. In countless ways, he and scholars like him positioned Africa on the global stage, affirming its relevance in the world of ideas and scholarship.

To a considerable extent, Professor Ogot was a staunch decolonial scholar who projected outstanding accomplishments of Africans in the past and the present, to ensure that Africa’s legacy was recognized and celebrated. While academics like him would have prioritized knowledge transfer as a means of intellectual empowerment, Professor Ogot did more than this. He was a mentor to many of us. If anything, he was able to show people ways to navigate the complexities of their existence and life, equipping them with insights to overcome the towering challenges imposed by history and circumstance. Across different African countries, one would find a handful of individuals who have directly or indirectly benefited from his mentorship—whether through personal interactions or by engaging with his work and ideas. Married and blessed with children and grandchildren, he can be said to have made a very profound impact in life because he provided opportunities for people to learn, grow, and leave their own indelible marks on the world. His life was not merely lived; it was purposefully dedicated to the intellectual and cultural empowerment of an entire continent.

A giant tree has fallen, and we are grieving. History is grieving. African scholarship is grieving. Till we meet again, keep resting in the Luo soil, keep resting, my dear Professor Bethwell Ogot.

Thanks so much indeed Prof Falola for this insightful tribute to the late Professor Ogot. I never met him but Professor Leonard Ngconco, who taught me African history at the University of Botswana in the 1990s and belonged to the same generation as Prof Ogot, did make reference to Prof Ogot’s contribution to African historiograophy through documentation of History of the Luo people of Kenya using oral sources. Quite helpful stuff

We have lost a Great Historian and an Academic Icon. Prof. Bethwel Ogot believed in the “History of Things” and his life signifies and epitomizes History. May our History Teacher and Mentor Rest in Peace Eternally. To his Dear Family and Prof. Madara Ogot to whom I know personally, I pass my sincere condolences. To us all we are reminded by the Stoic Philosophers on the impermanence of “Things” and Human life; and the memories and legacy of all is all History in the realm of the universe. Rest in Peace our Dear Teacher, Mentor and Friend as your work and legacy will live on. By Anne Nangulu

AMEN to the prayers. Could and can the African identity have been fully and truly formed without external input or exchanges?

Are we not now in the danger of over Africanism as we were in danger of over colonialism?