By Toyin Falola

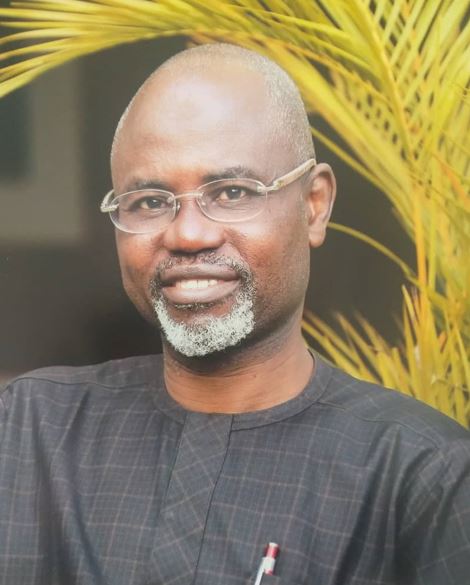

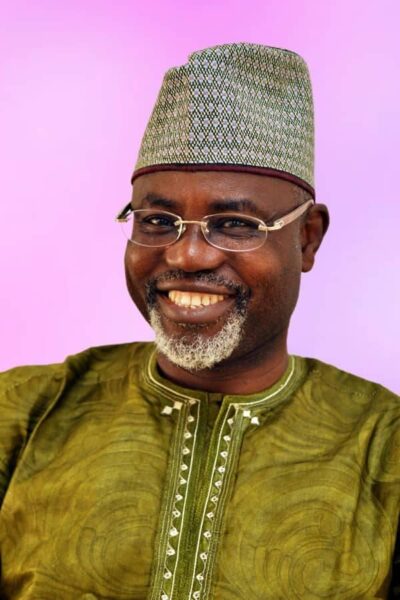

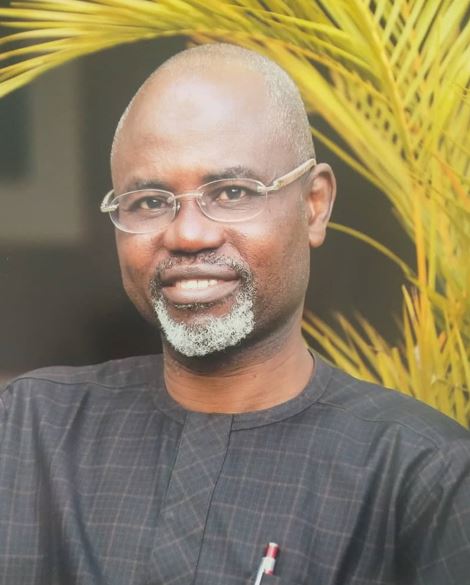

One of the defining attributes of a sage is their ability to meditate on present events and dig into past actions for cross-examination of issues and emerging trends to provide a clear roadmap for the future. While many professors undergo a strenuous process to develop this quality, some have the ability without struggling. Among that latter category is Professor Wahab Egbewole, an enigmatic personality with robust ideas that are beneficial to humanity.

Recently, Professor Egbewole noted that Nigeria’s post-independence development, anchored on solid educational foundations, reflects the inherent awareness of the front-runners of the country’s nationalist advocacy that without quality education, dreams and aspirations for the country’s greatness would remain mere illusions. He recognized the efforts of these early generations in facilitating unprecedented transformations, and they have done well, and history continues to praise them.

Professor Egbewole opines that although the post-independence educational structures of the country retained the fundamental principles employed by the colonialists when establishing the various educational centres, their focus shifted significantly. He admitted that this shift was necessary because the priority then was not how Nigerians provided educational services to the teaming populace but more about when they would rid themselves of colonial influence. Professor Egbewole, however, believes that each phase of development requires different thinking, as it is customary for human societies to evolve to accommodate changes. Basically, the current time, in which technological and scientific innovations have been overtaken, departs ideologically and culturally from the previous systems. It is crucial to come to a common agreement on how best to adapt to these changes to avoid vulnerability in the larger scheme of things.

Meanwhile, amidst the attendant changes engulfing the world currently, Nigeria is confronted with numerous peculiarities that necessitate a thorough revaluation of its approaches and principles. Given that the changes necessitated by the technological surge demand another level of attitude from the people, they must be prepared, as the changes occasioned by artificial economic schematics could have unpredictable and lasting negative effects.

For instance, Professor Egbewole cautioned against arguing or concluding that the removal of subsidies, which exacerbates economic meltdown in the country, is a deliberate machination imposed by the government to taunt innocent citizens. He encourages the populace to instead see subsidy removal as an inevitable decision reached after realising that subsidy payments have become a substantial financial burden for the government. In all fairness to common sense, this dilemma is one that Nigeria cannot escape from in its current trajectory.

This piece does not replicate what Professor Egbewole has said in his well-thought-out work but rather reinforces the argument that he is clairvoyant and can provide accurate information, judgment, and perspective based on thorough analysis. Through his piece, he aims to show how the elites, who gained access to the corridor of economic power either as a political favour or compensation for an earlier act of kindness, have compromised the nation’s future. These elites have failed to recognise that competing globally is only possible for a country like Nigeria when its leaders, irrespective of the category of leadership, have the discipline to showcase collective seriousness.

By their depleting moral principles, the country became a victim of its elites, and they appear to pay no particular attention to the best ways to rejuvenate the nation. Professor Egbewole argues that the country’s persistent problems stem from a network of an ill-conceived fraternity dominated by the elites, who intend to continue to take advantage of the government through the oil subsidy scheme. They understand that continued subsidy payments draw substantial amounts of funds from the country’s coffers and could lead to an economic breakdown, but they are more concerned about their exploitative opportunities than the national project. When the current president took decisive action to end this scam, beneficiaries fought back fiercely, holding the country by the jugular in the process.

Knowing that education is critical to any form of development, Professor Egbewole contextualizes all these challenges to how changes in governance, as propelled by subsidy removal, could affect university management and the country’s educational system. Among other things, Professor Egbewole emphasizes that the issue of governance and management is crucial at this pivotal time for revamping the country’s educational system. This awareness informs his position that although there could be daring economic challenges imposed by the policy initiatives introduced by the government, effective institutional management entails careful consideration of various factors.

Notably, the orderliness enjoyed within the school setting results from continuous interaction among different mechanisms and components of leadership. For example, while the vice-chancellor is typically known as the central face of the leadership of schools, the responsibility for advancing the institutions does not lie exclusively with them. Bodies like the Governing Council, the Senate, and the Congregation, among others, each has its responsibilities that must be adequately carried out for the effective running of the system. Here, Professor Egbewole’s concern is that unless these different components work together effectively, it becomes almost impossible to enhance the quality of education in an economically wounded country.

In all honesty, if the current government, regardless of its political power, does not compound the existing challenges within the educational system and instead allows its organs to function independently with only necessary guidance and motivation, it can create an atmosphere conducive to the dissemination of quality education to students while simultaneously enhancing the quality of students, staff, and society. This approach would undoubtedly pave the way for several other things, all of which would lead to the actualization of the country’s potential.

While the government has given reasonable justification for the removal of subsidy, the fiscal benefits that would come from it should be maximized effectively. For instance, nearly all schools in the country suffer from various infrastructure problems. Some are faced with unequipped classrooms and laboratories, while others face a shortage of personnel essential for the sound development of students. It is an undeniable reality in many Nigerian universities that infrastructure deficit often contributes to poor academic outcomes among graduates. Many students, particularly those in Pure Sciences requiring necessary exposure to practical experiences and knowledge, are frequently disappointed by the suboptimal resources available in their schools. Failure to address these issues will inevitably lead to critical challenges.

Professor Egbewole offers valuable insights into the management of student affairs in Nigeria’s current academic system. According to him, students in contemporary times should be the focal point of all educational engagements, and it is important to give them the necessary support that would stimulate their learning. Professor Egbewole identifies a couple of challenges facing students in modern times, including the disproportionate number of students seeking admission compared to available universities. Government-owned universities are overloaded with excess students, yet their needs are not adequately provided for. For example, an increased student population logically requires a corresponding increase in staff, but Nigerian lecturers are over-laboured, making it difficult to provide necessary services such as counselling and mentorship. This further complicates the students’ prospects and undermines the country’s development potential.

Professor Egbewole stresses the importance of providing student support services, as that will considerably influence students’ engagement. Without creating such a friendly atmosphere for them, they will lack the motivation to collectively work toward the country’s transformation. All these insights give us a reason to celebrate the academic ingenuity of this well-versed Professor, as he clearly understands the measures needed to address Nigeria’s educational challenges.

PS: This is the third of a three-part essay inspired by Professor Wahab Egbewole’s lecture on June 3, 2024, at the University of Abuja on university administration in post-subsidy Nigeria. I would like to extend my gratitude to Sulaman O. Nafiu of the El-Mavericky Centre for Educational Research and Development, who extended the invitation to Professor Egbewole. Nafiu’s commitment to the transformation of Nigeria is commendable.