Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju

Toyin Falola, left, and wife, right, with another celebrant, middle, at an event in honour of Yemisi Shyllon

SOAS Library, University of London. 2024.

I kept seeing one name recurring on various shelves, dedicated to different disciplines.

That was how I first came across the name of Toyin Falola.

Who is this wondrous person? I asked my teacher Akin Oyetade.

He stated that he too was amazed at the phenomenon.

Institute of African Studies, University of Cambridge. 2009.

I was conversing with a visiting academic from Nigeria whose discipline was History.

“How would you assess Toyin Falola?” I asked ” against the background of such stalwarts of African history as Ade Ajayi, Kenneth Dike and others?”

“Falola has achieved more than all of them put together” she responded.

An outdoor bar in Lagos. 2020 perhaps. Falola excuses himself to pee in a corner created for that purpose.

We discuss the possibility of my taking a picture of that place where he is easing himself, contrasting it with the elite environments of the University of Texas, where he lectures.

His eyes gleaming, he is delighted by the idea of my taking such a picture and writing about it to be publicly shared.

He delights in reveling in the uniqueness of Nigeria in his regular visits to the country.

This is a man who took part in the famous anti-colonial Agbekoya Revolt as a messenger for the indigenous army fighting the British colonialists.

The first chapter of Decolonizing African Knowledge: Auto Ethnography and African Epistemologies( 2014).

Falola describes his powers of memory as an outcome of magic, through a ritual conducted on him to enhance his memory by his childhood mentor, Iya Lekuleja, “elderly female seller of assorted items for spiritual work”.

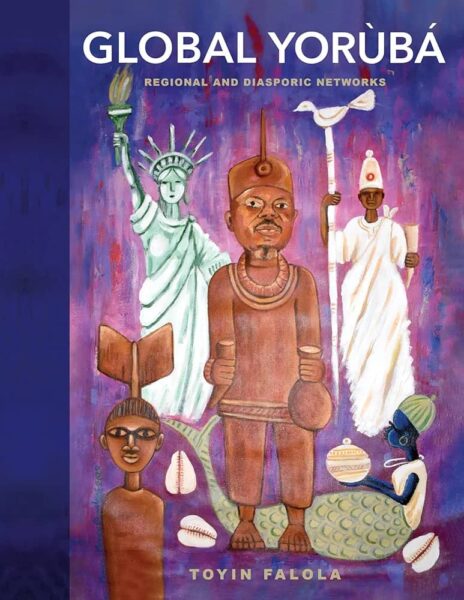

The cover of Yoruba Global: Regional and Diasporic Networks, Toyin Falola ( 2024).

Falola is shown between the US Statue of Liberty 🗽 and an image of Orunmila, the god of divine wisdom in Yoruba origin Orisha cosmology.

The deity holds a staff and what looks like an ofo horn, which Falola also holds, suggesting parallel enabling of power with the deity, the horn understood as a means of magically amplifying and focusing the power of speech, enabling it do wonderfully unconventional and transformative things.

In his other hand he grasps what looks like a bag of oogun, medicinal or magical preparations, or both, while at his feet can be seen a sculpture of the god Shango and an image of a mami-wata, a mermaid, holding a covered calabash, while at the bottom of the tableau, cowries are strewn, once a form of currency now a ritual implement.

Why is a scholar in the Western academy, a PhD in history and a Professor of the Humanities, depicting himself in the form of an adept of Yoruba spirituality, possibly operating between the US and the Yoruba homeland?

Are there things we do not know about him?

About how he seems to have merged many lifetimes into one?

Falola’s house in Nigeria. December 2024. I arrive early in the morning to find him seated in front of his computer where he takes breakfast in my presence.

I have been up all night, he states, as I watch the display of text of writing by him on various windows on his computer.

If one is ready to so use oneself, what may one not achieve?

But how may one achieve balance between such self propulsion and the needs of one’s biology?

I once thought I knew strategic secrets of this man’s creativity.

I still believe I do.

He does things many others can do but choose not to do.

Most humanities scholars do not write about other scholars.

That aspect of Falola’s work, from essays to books, constitutes a library of its own.

Most scholars treat their research sources simply as raw material.

Falola organizes them into edited books.

Most scholars do not seriously pursue an expressive skill outside their scholarship.

Falola is a serious poet.

Any literate person can write about their life but most don’t.

Falola has had two substantive autobiographies published.

Most humanities scholars are lone rangers.

Falola is a great collaborator, merging the skills of others with his.

Many scholars do not promote other scholars.

That activity is a central part of Falola’s work, involving conferences and books, such as those on Nimi Wariboko.

Most scholars will not involve themselves in such initiatives as interviewing other people.

Falola has a robust catalogue of interviews.

Most scholars do not devise publishing strategies in collaboration with publishers.

Falola has diverse book series with various publishers, from Bloomsbury to Cambridge and more, series to which he contributes at least one book.

What, however, are Falola’s limitations?

He is very bold but in some instances, overcautious.

He is careful not to venture into depth discussion of the sciences, leading to significant inadequacies when doing so, as in his conflating witchcraft history and beliefs in the West with that of Africa and assuming existing or possible contributions of African magic to science the way that Western esotericism contributed to science, ignoring the strategic differences between the highly systematized, richly theorized, copiously scribal and highly experimental character of the Western esoteric tradition as opposed to the largely oral, inadequately theorized character of much of African magical beliefs as he seems to do in Sacred Words and Holy Realms, if I recall the book title and the relevant section correctly.

Summation

I believe academic studies could benefit from the Falola model, moving from siloed styles of doing scholarship to the variegated yet deeply exploring approach of a Falola.