Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju

Toyin Falola’s’s “The Dreamer’s Odyssey’ (https://toyinfalolanetwork.org/the-dreamers-odyssey/) is an elliptically beguiling poem, celebrating the life’s journey of art historian Chika Okeke-Agulu, at a climatic point in his career, climatic, keeping in mind that other climaxes may follow in an ascending sequence of mountain peaks.

It is a beautiful poem about a steadfastly determined scholar.

To adequately appreciate the poem, however, in its eloquence, evocations and silences, one needs to know the specifics the poem is alluding to.

The poem would benefit from an expository accompaniment, like the poems with essays in Falola’s In Praise of Greatness: A Poetics of African Adulation.

This poem reads like a gnomic yet extended lyric form, depths concealed in images the direct referents to which few clues are provided.

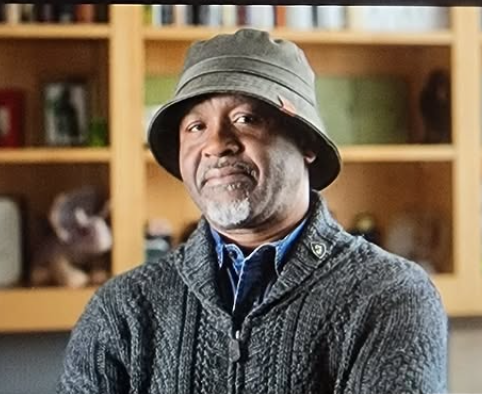

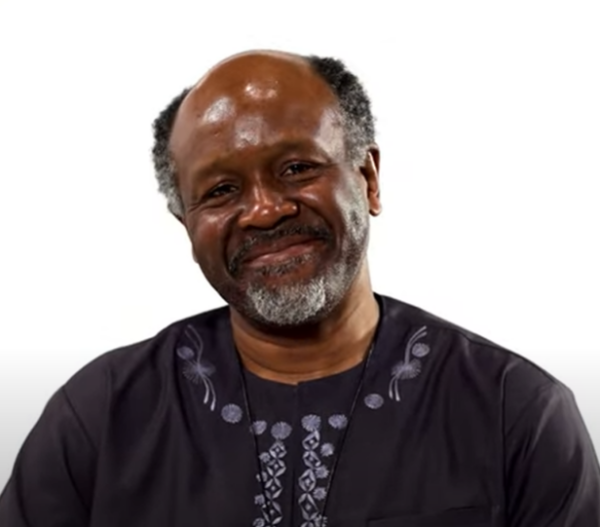

That hermeticism is part of the poem’s beauty and power, complemented and amplified by the sequence of elegant images of Agulu that punctuate the piece.

The poem, though, sounds like an oracular discourse, striking but allowing quite limited penetration into the specificities of the history it tells, limited penetrability bcs its underlying universe of reference is unknown to the non-initiate, the two initiates here being Agulu and Falola, on account of the extensive sensitivity demonstrated by Falola in managing the relationship between interior and exterior worlds in the evolution of Agulu ‘s life.

Beyond such opaque beauty, Falola’s poem cuts off the roots of its own discourse, like limiting the study of a tree to its crown without addressing the roots and stem.

The poem begins:

“A dreamer was born on a red space

where the town criers woke residents

with disastrous news of buried casualties

yet survived the storm with only his dreams

the dreamer dreamed where dreams

were murdered in sequence

and flew beyond the Atlantic

to put himself on the map of success”

Clearly the poem is evoking Agulu’s migration to the US where he eventually became a professor at Princeton.

But can the achievements represented by that relocation across the Atlantic be adequately understood apart from.the roots Agulu was coming from, roots which seem to be referenced in the poem only in terms of the murdering of dreams from which the subject fled to an environment where “dreams and realities stay”?

Is it possible to adequately understand Agulu’s academic history and its influence on him and its resonance in his later work, as well as the trajectory of his scholarly career and its contributions to art history, criticism and theory without a grasp of his academic and scholarly foundations at the art school of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, well before his migration to the US?

Agulu might be the most prominent art

scholar from the Nsukka art school while El Anatsui is the most internationally prominent artist from that school, trajectories intertwined in their journey to the top.

Agulu’s two most strategic books might be Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria( 2015) and El Anatsui: The Reinvention of Sculpture, 2022.

I don’t know if any of his two other books known to me achieve the same level of ideational, historical and critical scope of those works.

El Anatsui: The Reinvention of Sculpture is described in its back cover blurb as the outcome of thirty years of “research, scholarship and close collaboration with the artist” , while in the preface, Agulu states “Anatsui…was my art school teacher, then studio master, and later a senior colleague at the University of Nigeria”.

Those words encapsulate a universe, aspects of which are evident in the book and in his Nigerian Modernism, aspects telescoped into Agulu’s programmatic essay “The Quest : From Zaria to Nsukka” in Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa ed. by Clementine Dellis.

That universe is represented by the ferment embodied by the “Nsukka” of the essay’s title, and the effects of the journey of one man, Uche Okeke, from what later became Ahmadou Bello University, Zaria to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, bringing with him the philosophy of “Natural Synthesis”, which, radiating from Zaria would lay the foundations for what is now known as academically influenced modern African art in Nigeria, seeding, catalyzing a creative ferment at Nsukka with such younger colleagues as Obiora Udechukwu, on whom Agulu has also published a book,Chike Aniakor and others, in tandem with such literary generators as Chinua Achebe in literature, creating an ecclectic scholarly and literary culture, in relation to an indigenous centred art and philosophical culture symbolized by the study of Uli, a classical Igbo artistic form demonstrating a visual, spiritual and philosophical resonance, intersecting with Nsibidi, the Cross River expressive system combining graphic signs, gestural symbolism and object arrangement into a synthesis speaking to social, philosophical and spiritual values.

That matrix generated a readily identifiable stamp in the artists and scholars of the Nsukka art school, where Agulu had his first degree and to which he returned to teach after his PhD in the US.

The creative ferment enabled by Uche Okeke and his disciples, from Chike Aniakor to Obiora Udechukwu, in one generation, to Olu Oguibe, Sylvester Ogbechie, Chika Okeke-Agulu and others in a subsequent generation, in which imagination and intellect, art, literature and philosophy were cultivated in unison, created one of the most successful art schools in Nigeria.

Agulu might not be the most expressively powerful of the alumni and teachers of the school and might not even be the most published, but he seems to have become uniquely positioned, beginning from his presence at Princeton, one of the world’s most prestigious schools, to his steady escalation of publications mapping the creation of what is now known as modern African art, culminating in his Postcolonial Modernism.

Everything Agulu has done since leaving Nsukka, perhaps in challenging circumstances hinted at by Falola’s poem,needs to be examined for its possible roots in his Nsukka journey, where he is likely to have been first introduced to the scholarly culture,the understanding of ideological, technical and historical currents of African art the study of which became his life’s work.

His later role on the editorial board of Okwui Enwezor ‘s Nka, created to project modern African art, the various art promotion initiatives in which he has grown as a curator and scholar, contributing to shaping the art world, his eventual pioneering recognition as the first African, if I recall correctly, to hold the Slade Professorship at Oxford, and his admission to the British Academy, are they fully graspable unless in the context of the ideological, disciplinary and historical matrices provided by his Nsukka experience?