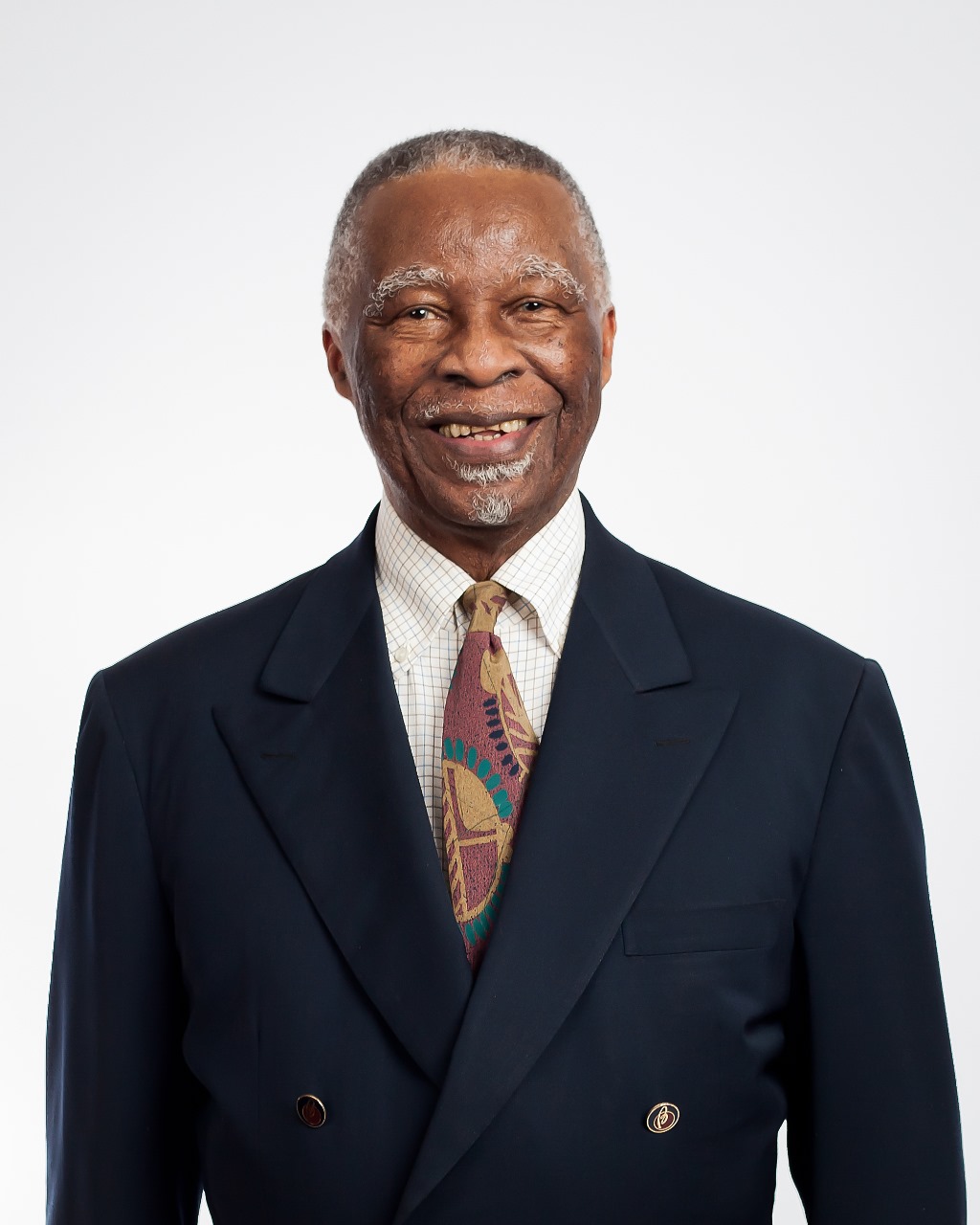

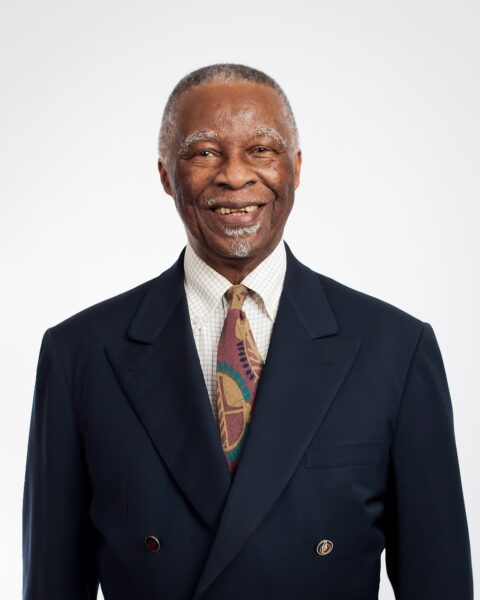

By Toyin Falola

Every country has a unique history, and recognizing this history is essential for constructing a formidable civilization that can stand the test of time. This explains why, despite the possibility of bringing efficiency, great people have always cautioned against adopting political or ideological philosophy based on their success elsewhere. Rather, such philosophies should be tailored to accommodate the peculiarities of a people if they intend to benefit maximally from it.

The stubbornness of people to put this saying into perspective accounts for the reasons behind the persistent underdevelopment of some groups and countries. No one discards the uniqueness of their past to formulate several alternative ideas in the hope that they would bring positive results without some negative outcomes. People who do that often risk unimaginable failure, for it is a general knowledge that once you undermine the influence of the past in what you do, you forgo some of the possibilities of achieving success.

South Africa’s experience is illustrative of this. Apart from facing colonial brutality and its oppressive policies, South Africans were one of the unlucky people to experience the painful hands of apartheid. Under apartheid, their humanity was degraded, and their integrity was assaulted. The onslaught of their identity metamorphosed into the erosion of their cultural values, which culminated in the extermination of many of their legacies.

As a result, while every nation emerging from colonialism must take bold steps to reclaim its past, South Africans faced the additional challenge of overcoming the deep scars left by apartheid. In settler colonialism, where oppressors forcefully integrated themselves into the organic system and foundational structures of the conquered society, the granting of independence to the victims did not automatically eradicate the pangs of colonial disasters inflicted by years of colonial exploitation. While countries that did not experience settler colonialism might find it easier to embark on a rapid process of renaissance, the situation is different for those that did. For the former, they would not have to tolerate the horrendous reality of the nagging presence of their erstwhile colonial lords, except for the intermittent feeling of emptiness that comes from the memory of the dehumanizing encounters with the oppressors.

For the settler colonies, however, their experience is not one they can easily dust off. For one, their independence has only occurred at the administrative level as they are compelled to remain tolerant of the people who subjected them to endless torture because of racial differences. Even without the power to resist white settlers’ domination, independence did not alter their fate in the economic system, as many still did not have the opportunity to own land bequeathed to them by their forebears. The worry thus continues. While they may have moved beyond the torture of being degraded and molested physically, sexually, humanly and ideologically, the memories of being considered less than humans, as well as the human psychology in them, continue to provoke feelings of disgust and self-loathing. This distress is especially acute when settler colonial imperialists refuse to leave.

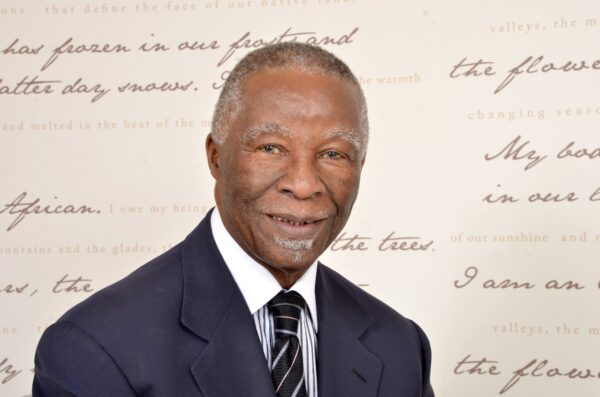

As Mbeki notes, nation-building in such an environment begins with an acute sacrificial disposition on the part of Africans who have faced debilitating problems at the hands of their white oppressors. It requires a lot of patience because it is naturally difficult to maintain a peaceful coexistence with individuals who subjected them to generations of torture and indignity. This requires a lot, and it explains why leaders of such a country should understand how to persuade their people to act with restraint.

Mbeki believes that conflicts are sensitive, and unless handled with a high degree of diplomacy, the consequences can cause contagion that may be difficult to tame. In a society that has experienced apartheid, people can become uncontrollable if their energies are not properly channelled toward positive transformation. They would have to restrain themselves and cultivate the habit of forgiveness because repeated hostile reactions will only generate more conflicts, making it impossible to experience growth of any kind. Therefore, one of the first and most critical steps is to foster an atmosphere where dialogue can occur between the white minority and the black majority, discussing the paths forward for nation-building. This conversation is essential, as it clarifies the roles each of them must play in the process.

Mbeki recognizes the key components of building a functional society in South Africa, with one of the most crucial being the creation of a non-racist society that accommodates all, irrespective of their racial genealogy. It is imperative to reiterate that South Africans do not have claims to any other place in the world except for their country, bequeathed to them by their forebears and one they intend to pass on to the generations yet to come. This mindset must be deeply ingrained in their political life and internalized by every member of society. Such an orientation is important because it would etch in their hearts the understanding that they cannot afford to see their country crumble. If South Africa were to be destroyed, the people would face serious and detrimental consequences. The painful history of the past must be balanced with the painful reality of the present.

With the knowledge that many conflicted minds may feel negatively offended by this proposal, Mbeki reinforces his position by highlighting the interconnection between holding onto the past and the country’s inability to meet contemporary challenges. Many remain trapped in the limbo of self-abnegation. Moreover, when a society refuses to progress, it inevitably undermines its own personal and collective development.

Growth in South Africa must involve a deliberate effort to address the poor legacies inherited from the apartheid years. Poverty has become almost synonymous with many black South Africans because of the inhumane policies designed to impoverish the people and take away their dignity. Mbeki suggests that the most effective way to triumph in such a condition is to ensure that people come together to create a non-racist and egalitarian system where everyone can tackle the difficulties that confront them. The white population in the country has expressed their suspicions and fears about how the Black leadership in post-1994 South Africa might treat them. While their concerns are known, Mbeki reveals that their interest is in repositioning the nation on the path of development rather than pursuing self-serving ambitions.

Given the condition of the people, they needed to consider the most effective ways through which they could achieve their goal of creating a better society for all. South Africans must be free from fear and be free from poverty. Both objectives can be achieved only when the right policies are implemented so that they can have access to economic resources that will bring about their rise. The transformation of South Africa depends on the participatory politics that the people play.

Mbeki notes that the South African people embrace democracy partly because of the ideological underpinnings of their society and a deep-seated commitment to fairness and justice. Unlike many other African nations, both distant and proximal, South Africans transitioned from the apartheid system to democracy with an exceptional degree of maturity and discipline. They did not participate in actions that could signal an intention to repudiate the white minority or inflict maximum damage due to their not-so-palatable history. Instead, they chose a path of dialogue and established a culture of accountability, helping their people to understand the importance of harmonious relationships among diverse groups in society.

Being the main light in the Southern African region may not be enough to convince the world of their peaceful nature; therefore, the country’s leaders must actively invest in the restoration of peace in the region, which comes at a significant cost. Often, they have had to commit a substantial amount of human and financial resources for the restoration of peace in the region. For instance, they made frantic efforts to instigate the reconciliation process in Lesotho in 1999 when military forces overtook the country. Their intervention eventually restored democracy in the country, demonstrating a genuine commitment to nation-building.

I want to re-read many of Mbeki’s speeches and letters to see whether many South Africans see the fall of apartheid as an end to struggles and the attainment of freedom or the beginning of a new journey that entails a lot of work to bring about progress. The debate about the meaning of the fall of apartheid needs to be vigorous. Is it the end of a journey or the beginning of a new one with unseen forces and traps?

PS: This is a 12-part series based on the collections edited by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, titled ANC Today Letters: The Ideas and Thoughts of President Thabo Mbeki, Volume 1, 2001-2004, supplemented by materials in the Thabo Mbeki Museum, UNISA, Pretoria. The series is composed over five weeks in three different countries. The museum’s resources, digitized under 27 categories, can generate over 200 books.