By Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju

The Old Man and the Face of Wisdom

Comparative Cognitive Processes and Systems

“Exploring Every Corner of the Cosmos in Search of Knowledge”

Abstract

This essay examines the immediate and more distant yet strikingly illuminating implications of the use, in his books, in text/image collages and memorabilia of him, of artistic images of polymathic scholar, writer and institutional organizer Toyin Falola, exploring these images within an intercultural context, generating a global nexus in relation to their proximate African frameworks.

The essay initiates what is likely to be a new field of study, Falola iconography, the study of values relating to images of Falola, part of Falola Studies, the investigation of the life and work of the scholar, writer and academic entrepreneur.

This part of the essay focuses on a particular image of Falola in terms of the immediate and intercultural implications of the expansive understanding of discourse developed by Rowland Abiodun’s work on Yoruba thought.

A Theory of Discourse in Yoruba Thought Unifying Expressive Forms

The Yoruba expression “Ojú lọ̀rọ́ wà, one of its conventional translations being “the face is the abode of discourse” ( Pius Adesanmi), may also be rendered in more expansive terms as ”the face is the zone, abode, point of concentration, of those creative powers, mobile and dynamic, demonstrating the human capacity to make meaning of existence through reflection and expression, powers inspiring imaginative reference to distill their incandescent power”.

This rendering tries to maximise the meaning value, the semantic range, of the concept of ”ọ̀rọ́” in Yoruba thought, in relation to perspectives on the significance of expression across various forms, in diverse media.

This orientation ranges from the foundations of human expression in vocalization, to which “ọ̀rọ́” is particularly intimately related, to all forms of discourse.

It adapts Rowland Abiodun’s reproduction and commentary, in Yoruba Art and Language, of a story by an unnamed thinker in the Yoruba origin Ifa tradition who employed cosmogonic narrative as a means of developing a broader interpretation of the concept of ”ọ̀rọ́”, taking it beyond the basic understanding of a subject of discourse, a point of reference, to include a perspective on the origin of human discursive powers, of the human capacity for reflection and expression.

This narrative depicts “ọ̀rọ́” as a dramatization of the grounding of human expressive capacities in the divine origins of the universe, in the wisdom, knowledge and understanding of Odumare, the creator of the cosmos, potencies of Odumare through which all of reality was brought into being.

This depiction of the origins of “ọ̀rọ́” may be understood as implying a view on human reflective powers and even human consciousness that enables expression and its grounds in reflection. It may also be perceived as suggesting a stance on the sensitivity to the difference between self and other that enables expressions and its grounding in thought.

These possibilities are explicitly developed as well as evoked by Abiodun in relation to a series of Ifa narratives which incidentally amplify the idea of the role of the significance of the capacity for discourse, of the dialogical and interpersonal expressivity it enables, as strategic to the foundations of existence.

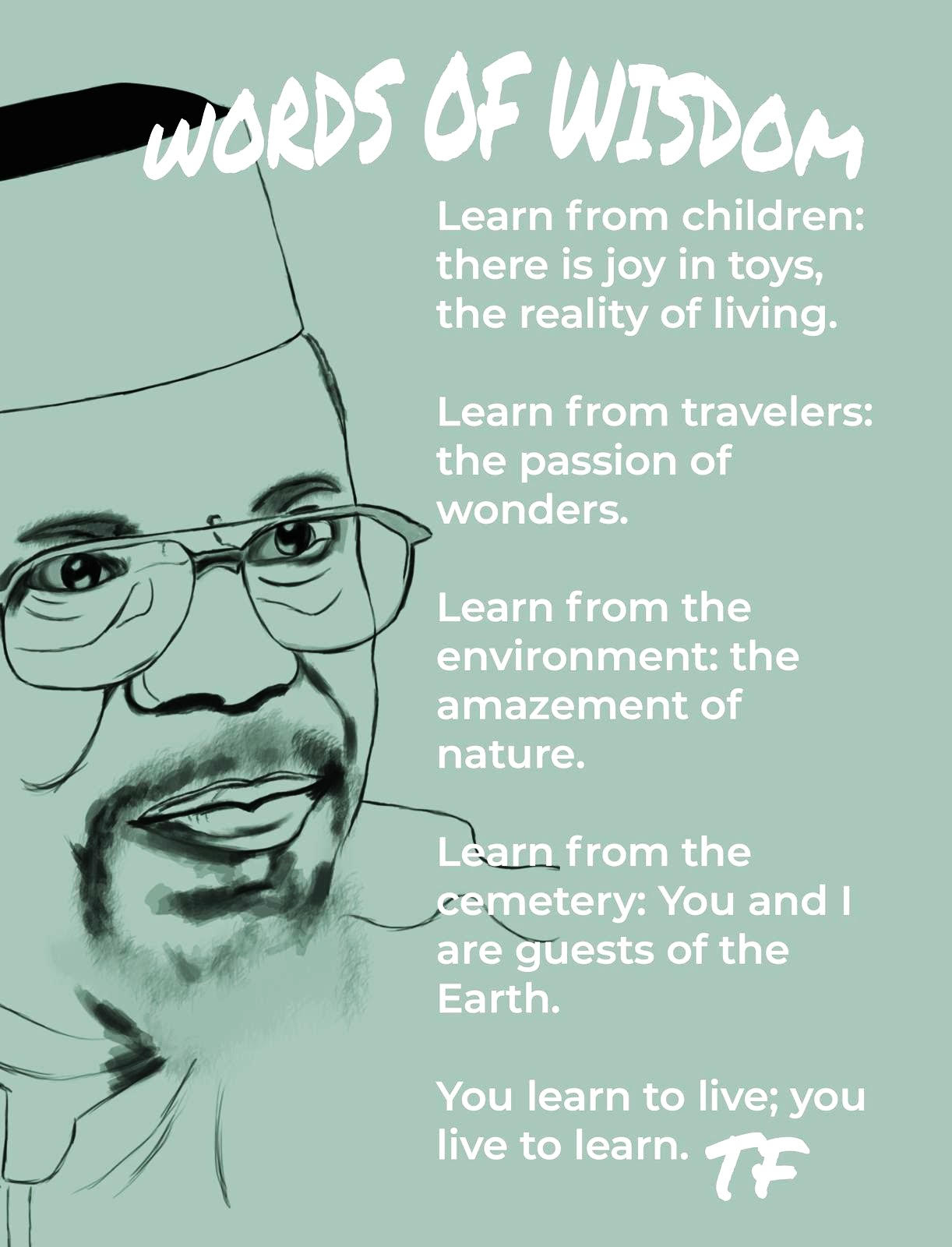

These considerations of mine are inspired by reflection on an aspect of Falola iconography, the use of images of scholar and writer Toyin Falola in evoking a range of values, specifically a collage of a drawing of his face alongside a poem by him, a convention more often employed in relation to religious figures than to writers and scholars, though scholars’ and writers’ vocations foreground writing from which such visual and verbal conjunctions could be made.

The image/text combination that inspires this essay is the cover image of the essay, also shown directly below, which I find the most accomplished in my experience so far of Falola’s use of this expressive genre, his poetry in collaboration with an image of his face produced by an artist, in terms of a drawing or a photograph, examples of which he has been distributing on the Falola Media WhatsApp platforms and on his Google groups.

I consider this particular image/text collage as the most accomplished beceause I see the text as achieving a blend of rich insight and expressive music far beyond the other examples, insightful as their philosipocical comments are, which are also presented at intervals in this essay. All of them, however, demonstrate significant power in their visual art.

From Scholar to Sage in Falola Iconography

What is achieved by the juxtaposition of a drawing of Falola’s face with a poem by Falola on how to live, a general summation on the good life, a broad philosophical statement comprising readily assimilated maxims meant to inspire reflection and action?

This is a visual juxtaposition of the face of a man of very mature yet vigorous years, shaped by lines mapping configurations of experience, with richly poetic text depicting a constellation of human experience, from childhood to adulthood, from mature years to the final transition represented by death.

This conjunction between face and text casts the figure whose face shares equal space with the poem as a sage. The map of lines configuring the face, in relation to the ideational sensitivity and imagistic beauty suggested by the poem evoke the expression of wisdom distilled from the life’s journey implied by the eloquent face.

Mobilities of discourse are thereby galvanized as word and image, drawing and text, come together to project a unified impression-a traveller of significant progress on the journey of life sharing wisdom distilled from the voyage, wisdom centred in the appreciation of life’s simple and immediate values- childhood, hospitality, nature, transience, continuous learning.

What can we take with us from one person’s efforts to foreground his own face in relation to philosophical thought?

Falola is not the artist of the various visual representations of himself evident in diverse media, from the text/image combination discussed here to his book covers and book interiors, the latter examined in previous editions of this essay series. Even then, the initiative for such consistent self projection would be his.

Questions of Purpose

Can it be seen as a form of egotistic self-celebration, a scholar taking the unusual step of recurrently foregrounding his own physical form, his face and full-length image, in relation to his work?

How realistic is it to see these efforts in terms of his exploration of the idea of the self as an archive, a zone of psychological and cultural intersection, of individual and group histories, as demonstrated in his Decolonizing African Knowledge: Auto Ethnography and African Epistemologies?

Perspectives on Perception, the Face and the Eyes from Islam and Hinduism

Islam

In “Hijab Aesthetics and Mysticism” I quote a description of Cyrus Ali Zargar’s Sufi Aesthetics : Beauty, Love, and the Human Form in the Writings of Ibn ‘Arabi and ‘Iraqi which “discusses a perspective exemplified by the Islamic thinkers, mystics and poets Muhyi al-Din ibn al-‘Arabi and Fakhr al-Din ‘Iraqi and emblematized by the Persian contemplative ‘School of Passionate Love’, which understood divine beauty and human beauty as one reality, leading the Persian school to advocate the practice, controversial in Islam, of gazing at beautiful human faces.

This aesthetic and metaphysical orientation is correlative with a heightened form of perception in which that which is seen and that which is deemed beautiful as encountered through the senses facilitates entry into the divine and supersensory, inspiring the use of erotic language in describing the divine.”

Hinduism

The Sensuous and the Sacred: Chola Bronzes from South India:Resource for Teachers, adapting the insights of Vidya Dehejia, states:

“Darshan literally means ‘seeing’. In the Hindu tradition it refers especially to religious seeing, or the visual perception of the sacred. The central act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to behold the image with one’s own eyes, to see and be seen by the deity.

Hindus believe that the deity is present in the image when invoked by temple priests. Viewing the image is an act of worship, and through the eyes one gains the blessings of the divine. By presenting themselves to the god for darshan, worshipers ready themselves for the grace and blessings the god may bestow on them”.

The Cognitive Possibilities of Human Embodiment and of the Motif of the Old Man

Demas Nwoko describes classical African aesthetics, distilling the thought of various thinkers and general perspectives on aesthetics, as recognizing the beauty represented by every stage of human physical development, including that of mature years beyond middle age, “the beauty of old people”, as he puts it ( “The Aesthetics of African Art and Culture”, New Culture, Vol. 1. No. 8, 1979, 4-6), an idea incidentally suggested by the Falola image motivating this essay.

Such a figure at the level of temporal development represented by the Falola image, the image of a thoughtful man of very mature years, is one of the archetypal forms of the human imagination, represented for me particularly by the combination of occult power and wisdom embodied by a succession of figures in English literature, Merlin, the wizard of King Arthur in the Arthurian cycle, Gandalf, the central wizard in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy and Dumbledore, headmaster of the wizard school Hogwarts in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Hammadi encounters an old man sitting at the top of a tree, gazing at the stars, in Ahmadou Hampate Ba’s Kaidara: A Fulani Cosmological Epic from Mali.

Why is he perched at the topmost branches of the arboreal entity, watching the celestial bodies? Is he seeking something in their patterns ? Some supernal wisdom, perhaps?

An African proverb states that what an old man perceives while seated, a young person can’t see from the top of a tree. What could have necessitated this old man climbing to the top of a tree and positioning himself there?

Hammadi addresses the elderly man politely and seeks advice on his quest for Kaidara, the one both near and distant.

The old man responds with cryptic admonitions, seemingly ultimately meaningless, but which Hammadi follows and which save his life and ensure a tragedy free return to his home, after years of searching, wealthy but without finding Kaidara.

Years later, a bent and dirty old man finds his way to Hammadi’s gate, seeking to eat with the now wealthy man, an audacious aspiration to the guard at the entrance of the house of the eminent personality, who tries to frighten the old man away with threats, until the man’s loud obstinacy attracts Hammadi’s attention, who grants his request of having a meal with himself, upon which it is revealed that the decrepit and filthy personage, his clothes infested with lice, is Kaidara himself, “a beam of light from the hearth of Gueno, the creator of the universe”, assuming that unlikely form in order to test the readiness of those he meets to look below the surface of reality for its truth.

Ibn Arabi is circumambulating the Kaaba, the stone Muslims circle as part of their pilgrimage to Mecca, the geographical centre of Islamic devotion, when he sees, amidst the immense crowd, passing in and out of the mobile assembly in a manner indicating a form both insubstantial and concrete, the Youth, neither alive nor dead, the attention of whom Ibn Arabi is able to secure, requesting to be his student.

“Study my cobblestoned form” the Youth responds, “there you will learn all you need to know, the movement of the circle from its starting point back to its beginning, the unity of the cosmos from its origins to its furthest manifestations in a oneness of being and becoming” as that opening section of Ibn Arabi ‘s Futuhat al Mahakiya, the Meccan Illuminations, may be summarized.

On leaving hell, Dante and Virgil encounter a man through whose face pours light from a constellation of stars of such beauty that anyone who does not perceive that celestial brilliance is thereby widowed, as Dante describes, in his poem The Divine Comedy, of the entry of his guide and himself into Purgatory, the realm of cleansing from sin in Christian Catholic cosmology.

The image of the wise old man as a guide into otherwise hidden knowledge, as Cato in Dante’s Comedy is a guide to the wisdoms of self purification preparing one to participate in ultimate reality, is one of literature ‘s universal motifs.

In choosing to juxtapose his face, in his 70s, with words of wisdom in an image/text combination, distributed through various online channels, Falola taps into this dynamic, unleashing allusive potential in relation to philosophies of the body, of the face, of the eyes, of the human person, as a convergence of possibilities both terrestrial and cosmic.

Previous Essays in this Series